Motto for Private Office and Cabinet Room: "Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles every knot - HM"

|

|

Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (1894–1986) British statesman and Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. He was nicknamed "Supermac" and was known for his pragmatism, wit, and unflappability. Here is his motto when at Number 10. Motto for Private Office and Cabinet Room: "Quiet, calm deliberation disentangles every knot - HM"

0 Comments

I have been thinking about my maternal grandfather John William Burke. He was a pit worker in Yorkshire, a ‘deputy’, a kind of foreman. He worked at Maltby Main Colliery, one of the UK’s deep mines, noted for a major disaster on 28 July 1923 which killed 27 men and injured many more, my grandfather among them. I am told it affected his lungs. Eventually the condition shortened his life. Maltby Main closed for good in 2013. My grandfather is listed as one of the witnesses at the investigation by Sir Thomas Mottram (H M Chief Inspector of Mines) which resulted in the report “On the Causes of and Circumstances attending the Explosion which occurred at the Maltby Main Colliery, Yorkshire, On The 28th July, 1923”.

I never knew him, and wish I had. John William Burke 1 March 1890 (born Shirebrook, Derbyshire) and died 24 June 1954 at Harworth (then Yorkshire, later Nottinghamshire). In my early life (I was born two years after his death) I was surrounded by miners and by the North Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire collieries. My recent research has reminded me of the terrible working lives miners endured, and the high risks to which they were routinely exposed. As a boy I was unaware of the demanding nature of their work. All I recall is that the miners living near us appeared to enjoy a good standard of living. This (I now see) reflected both the risks of the job and the power of their union - the NUM. Now, their existence and power are things of the past. In late 2012 the 540 employees at Maltby Main were given redundancy notices and its above-ground structures demolished in 2014. In our more aware age coal is a dirty fuel. Yet it made very many things possible. And those who worked down the mines deserve to be remembered.  Woodbrooke closed at the end of October 2023. All down to cost, apparently. This residential Quaker centre was established by - and in the former home of - George Cadbury, in 1903. I see that an invitation had been made for those who knew the place to send in memories, though I saw this only after the closing date. In 1979 I spent almost one term at Woodbrooke. I was a member of Sheffield (Hartshead) Meeting and 23 years old. I'd had a miserable (and unsuccesful) time at Worksop's Valley Comprehensive School, followed by six years writing benefit Giro cheques (anyone remember those?) in the DHSS. Then an unexpected possibility opened up, to read for a social science degree and a social work qualification at university. Sheffield Friends (in particular Irene Gay and Maud Bruce) realised that I could do with some help in making the tranisition: they asked the meeting to fund me to spend time at Woodbrooke. I can never thank them enough. Woodbrooke then operated a term-time community. I attended lectures and tutorials, and met people like tutors John Punshon and Parker Palmer (the latter a visiting tutor from the USA). The Priestman's were the wardens. All told, it was a wonderful place and atmosphere, and without the heavier self-consciousness of being Quaker that seems to have overtaken British Quakers in the decades since. Alcohol was banned: a requirement imposed by George Cadbury. But that did not stop students slinking off in groups to bedrooms after super to open a few bottles. And it was at Woodbrooke that I was introduced by a member of The Wee Frees - a distinct Presbyterian denomination in Scotland - to a Rusty Nail. It comprises equal measures of Scotch and Drambuie. I have occasionally drunk it ever since. At that time, Woodbrooke (and the wider Society of Friends) would reference some of the then recent shapers of Quaker thought, including Maurice Creasey and Hugh Doncaster, names now largely forgotten. In that glorious short but rich time for me, the days were full of thinking, discussion and conversation; trips out with other students, the odd crush, consumption of Quaker and Christian history and a profound sese of having been given a second chance.  Keynes’s in his 1930 essay ‘The Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren’: “The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.” “… a somewhat disgusting morbidity…”. Brilliant phrase in that context. Dear Chums: I struggle with the sending of Christmas greetings, aware that for many of my friends they carry little metaphysical significance and because the money they generate for commercial printers and the Post Office can so easily find better application. Forgive the bah humbug moment. Instead I send this message by the modern miracle of email, and with all the good cheer I can muster (today, a good dose: I hope your internet connection has enough bandwidth). If I owe you money, its in the post; if I have not seen you for a while, I hope that can be remedied. With love/best wishes/fraternal greetings (delete as you think appropriate). And very best wishes for Christmas and the new year, Hugh

Not long after I began social work it was common to hold generic caseloads comprising children and family cases, older persons, mental health clients and various supervision order cases. I liked the variety, though it was soon to be replaced by specialism as part of the response to greater concern about child protection. Older persons' cases were often for assessment, followed by various services such as Home Help, Day Care or respite or residential care. An assessment would cover a range of psycho-medico-social aspects. One aspect to address was continence, or rather incontinence, and whether it was single or double. I know, exciting stuff. Many years later, after I had opted for specialist children and families work and had no continuing professional cause to consider incontinence of any kind, the term suddenly found a new use in my thinking. I have often reflected on the endless volume of words some people spout, and in a flash I saw this as a new and pernicious form of incontinence. 'Incontinent of speech' became an apt (but private) description for various people I encountered. They seemed unable to shut up, dribbled uncontrollably, and mostly inept in the ability to listen. I later came across the wonderful term, to 'overtalk' and posted about that here. Some people link the overtalkers - those who are 'incontinent of speech' - with the arrival of social media platforms. For sure these provide additional avenues for endless gas-bagging, but the condition was already at epidemic levels. What is it that makes a substantial proportion of the human race gas on so much and listen so little? They have as little control over what constantly spouts from their vocal chords as the traditionally incontinent do over their sphincters. New pages here about the Church in the East End.

I was ordained 34 years ago today. A clichéd observation, I know, but it seems like only yesterday. It also seems a very long time ago. The newly ordained tend to be overwhelmed by the experience; indeed, it is a wildly significant moment and transition, usually the fulfilment of several years hard work and preparation, spiritual and intellectual. For all but the die-hard evangelical ‘minister’ type, it marks a transition of an ontological kind: something that fundamentally alters one. It is not a job taken on; it is a new life embarked upon.

I am very far from being a die-hard evangelical. Nor am I a high Anglo-Catholic. I did reckon the moment of ordination to be of significance, and to represent a radical (i.e. far-reaching and irrevocable) handing-over of who and what I was – and who I might become - in the service of the Nazarene and His church. That has not changed, though time, observation and experience have changed my view of the church. Interestingly, it has deepened and simplified my following of the Nazarene. Inevitably, the years have shown me the unattractive (but not surprising) aspects of the church-as-institution: egoism, careerism, corruption, mediocrity. They have also acquainted me with the contrary: humility and loving kindness, modesty, faithfulness and superiority of character and conduct. I am grateful I actively served the institution for more than three decades whilst concurrently working in so-called secular jobs. Hugely grateful. This ‘dual’ aspect rooted me. After a monumental struggle, I finally got a face-to-face appointment with a GP. But it turned out that Dr XXXX did not go in for much face-to-face contact except with her computer screen. I wondered if she might in fact be an automaton or an AI bot for the amount of personal interaction she engaged in with me. I didn’t think to check her for a pulse, and anyway, I was the patient. I asked if we might also do the ‘repeat prescription review’ which was booked for the following week – for a medication that was not unrelated to my presenting symptom. I was promptly, and I thought rather harshly, told that an appointment can last only ten minutes, and which did I want her to deal with, the symptom or the repeat prescription review? I opted for the former, but felt slapped down. Indeed, the whole experience left me feeling rather atomised, an easily separated collection of bits rather than a single human being. Is this what General Practice has been reduced to?

I got what I had hoped for: a referral to an ENT specialist. And since we had two minutes left, I asked if she might do the repeat prescription review. By her own time-and-motion logic, there was no obvious escape route for her, and she said she would mark the request for release. Altogether an unhappy experience of being treated as an object to be processed. She did not examine me at all. But I examined her, with all the close attention of a patient treated as an inconvenience. IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY - John Betjeman This is, of course, a satirical composition in which John Betjeman imagines an upper class woman attending Evening Prayer in Westminster Abbey during WWII. It is clever, and uncomfortably true. True not only of the class and disposition represented, but of the distorting mess so many of us make not only of our prayers but also our ideologies and professed attitudes. It is a lifelong process of interrogating ourselves before we begin to see, then transform, our often self-centred positions. Surely one of the purposes of prayer. Click Read More "Get over yourself", when said to us by another, is often (usually) said as a rebuke, in anger, and is hurtful to hear. But the useful thrust of that perspective, when we can say it to ourselves, lovingly, is about the need to transcend our ego (something we all have). I found this helpful approach from Bertrand Russell: "Make your interests gradually become wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river — small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being." Visitors to these pages (that may only be me) will have spotted various posts that excoriate sentimentality. It is a fake and devaluing response to the challenges of life. It is rife. And so I was glad to come across this in Roger Scruton's 'Confessions of a Heretic': The Czech novelist Milan Kundera made a famous observation. 'Kitsch,' he wrote, 'causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: how nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass!' Kitsch, in other words, is not about the thing observed but about the observer. It does not invite you to feel moved by the doll you are dressing so tenderly, but by yourself dressing the doll. All sentimentality is like this: it redirects emotion from the object to the subject, so as to create a fantasy of emotion without the real cost of feeling it. The kitsch object encourages you to think, 'look at me feeling this; how nice I am and how lovable'. That is why Oscar Wilde, referring to one of Dickens's most sickly death-scenes, said that 'a man must have a heart of stone not to laugh at the death of Little Nell'.  I admire William Stringfellow and have written about him before (links below). Here is what he says about the corrupt use we too often make of language - what he calls Babel which he says "means the inversion of language, verbal inflation, libel, rumour, euphemism and coded phrases, rhetorical wantonness, redundancy, hyperbole, such profusion in speech and sound that comprehension is impaired, nonsense, sophistry, jargon, noise, incoherence, a chaos of voices and tongues, falsehood, blasphemy. And, in all of this, babel means violence…" In short, this is how we use language - personally, corporately, institutionally. Who amongst us is guilt-free in this corruption of communication? Also in William Stringfellow's words, hints of the antidote: “Listening is a rare happening amongst human beings. You cannot listen to the word another is speaking if you are preoccupied with your appearance or impressing the other, or if you are trying to decide what you are going to say when the other stops talking, or if you are debating about whether the word being spoken is true or relevant or agreeable. Such matters may have their place, but only after listening to the word as the word is being uttered. Listening, in other words, is a primitive act of love, in which a person gives self to another’s word, making self accessible and vulnerable to that word.” from his Count it All Joy.

Every night, as I fall asleep, I pray for people I know (and some I don't know) and always ask for an ending to suffering – human, animal - in all its forms. And invariably I ask God (the assumed recipient of these thoughts) why suffering should exist at all. No answer has arrived.

I keep the feast of Joseph the Worker because my own vocation to serve as a priest arose in the context of my ordinary, paid, work and, with the support of the church, led me to become a ‘priest in secular employment’ as that same church rather sadly describes it (I say ‘sadly’ because, really, there can be no distinction in the Christian mind between ‘sacred’ and ‘secular’, for all is God’s and God is in all). Here

Once upon a time, when travelling on a train, an announcement would be made about 'the next station'. A few years ago, announcers started speaking of 'the next station stop'. This week, on LNER, it had become 'the next calling point will be...'. What I want to know is where all this linguistic incontinence and showiness is formulated and decided upon?

It is getting on for ten months since I finished paid work. 'Retired' in popular thinking, but not in mine. The word is misleading. I tell people who ask that I have moved into 'post work liberation' - PWL. That could not be more fitting: the overwhelming experience is indeed one of liberation. I speak as someone who has been in paid employment since the age of 17, save for four years at university in my twenties. So it has been a long working day of just shy of fifty years.

Oh, you thirsty of every tribe

Get your ticket for an aeroplane ride Jesus our Saviour is coming to reign And take you to glory in his aeroplane I did not know of The Watersons, or of this fab song and sentiment. "....in the 1930s, [you'd hear] what they call a “brush arbour hymn” in the backwoods districts of America. Itinerant evangelists of a kind too modest to use a big tent might select a clearing near a spring and get helpers to build a “tabernickle” consisting of a framework of poles roofed over with leafy branches and lit by kerosene or petrol lamps. Advertisements seen at mountain filling stations as recently as 1976 say: “Please come and bring a carload of unsaved”... What gets sung is a mixture of standard hymns filled out with punchy choruses and more or less local compositions of touching naivety. Hymns using symbols from the world of mechanical transport have a venerable enough lineage. The long-lasting favourite Life's Railway to Heaven was widespread on broadsides in both USA and England in the mid-nineteenth century." Listen (above), and follow the lyrics (below). Have your Boarding Cards ready. And a happy Christmas to us all. Oh, one of these days around twelve o'clock The whole wide world will reel and rock The sinner will tremble and cry for pain And the Lord will come in his aeroplane Chorus (after each verse): Oh, you thirsty of every tribe Get your ticket for an aeroplane ride Jesus our Saviour is coming to reign And take you to glory in his aeroplane Oh, talk of rides in automobiles Talk of fast times in motor wheels We'll break all records as we upwards fly For an aeroplane joy ride in the sky You must get ready if you take this ride Leave all your sins and humble your pride Furnish a lamp both bright and clean And a vessel of oil to run the machine When our journey's over and we all sit down At the marriage supper with a robe and crown We'll blend our voices with a heavenly throng And praise our Saviour as the years roll on "Anthropathological enmeshment the common experience of (i) finding oneself in a difficult, painful situation; (i) recognizing the high costs, perhaps impossibility, of extrication, and (ji) experiencing a sense of impotence. An example might be that you are stressed by working conditions but are trapped by financial constraints and, even as you visualize an escape, such as downshifting, you recognize that such a move will simply enmesh you in a different set of difficulties.

Most of us are enmeshed in the conditions of capitalism but recognize that the alternatives of homelessness, voluntary austerity, communism or anarchism also have their unattractive aspects. Arguably, we are all systemically enmeshed: the whole world is faking it, and everyone is complicit in everyone else's frauds" (Miller, 2003, p. 120). Paradoxically, the ensuing sense of impotence may save us from worse anthropathological loops. Have you noticed how, in recent years, an obsession with 'leadership' and 'leaders' has crept into much discourse (and fantasy) about business, the third sector, the public sector and even the churches? It's a great bore. Organisations need competent managers at every level, and those in such roles will, inevitably and necessarily, influence, shape and 'lead' developments in those organisations. But what seems to have happened is that this essential function and aspect has now become personalised into 'a leader'. This is ego-talk. Many find it irresistible.

In the church (I am mostly familiar with the Church of England) the 'leadership' fetish has grown apace. A small example is the growing number of church websites that now list the clergy as 'the leadership team' - and I have seen some that locate them in 'the senior leadership team'. Frankly, it's all so desperate. What should be fellowship often seems now to be follower-ship. To have leaders, you need the led. There is a place for this where it is operationally and functionally necessary for tightly defined outcomes (think uniformed services and organisations with precise functions and outcomes). But in Christian communities it can only produce drone-disciples who surrender responsibility for their own Christian life to the 'experts', the leaders. And don't think that the ghastly cliché about 'servant-leader' avoids the pitfalls and dangers. I recently attended a mandatory safeguarding course, attended mostly by clergy and with some churchwardens. The (very competent) facilitator had, as part of her input, referred to the role that power and power-imbalances play in church abuse, and had illustrated this by some high-profile cases. As the event progressed, I was struck by how often 'leader' and 'leadership' were used by participants - in a sometimes slightly self-aggrandising way ("As the leader of my parish..."). I pointed this out, this link with what we had been told and how the conversation was going. There was some agreement, but others thought the two things were quite separate. Mainline church denominations 'embody' power relations and differentials in various ways, some subtle. Priests and bishops over laity, for example. Church architecture is another (the sacred sanctuary and altar, with the laity in their theatre-like pews). And another is found in who may speak and who is required to 'reply' following a set script. These are aspects of liturgical exchanges and liturgical life. I set these matters out bluntly to illustrate dimensions we often don't see clearly. There are many clergy who operate within these structures with attentiveness, humanity and sensitivity, and who mitigate the more dangerous aspects of the leadership fetish. They focus, first, on being disciples. But there are some clergy who don't. And there are laity who like to be 'led'. That does not make for mature Christian explorers. Tomorrow is Remembrance Sunday in the UK. I shall call to mind the uncle after whom I am named, who was shot down over the Netherlands on 20 September 1943. I shall remember also the countless souls not known to me, who died as a result of human ambition and violence. Here is a telling voice: that of Jacob Bronowski. It is the concluding sequence of his 1973 BBC series The Ascent of Man. It is said that this scene was unscripted and unrehearsed by him. "The words just came to me" he was quoted as saying. I do like it when new descriptions bring to light realities one had sensed but not consciously 'seen'. "Quiet Quitters" for example, defined as those who become disillusioned with their jobs and workplaces and give up putting in additional effort. They do the bare minimum. I used to think of them as 'time servers', but quiet quitters sounds useful. And now we have "loud labourers". Yes! We have all encountered them, and now the penny drops! These are the people who spend more time talking about the amount of work they do than doing it. Braggers about their busy-ness. My, I've met many such people in a variety of settings. Tiresome people, and rather easily seen through.

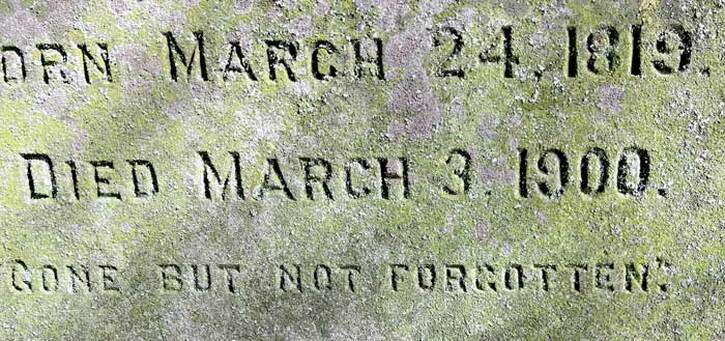

Today I visited one of my favourite silent places (see this post) and as usual found it empty, and so welcome and welcoming. Although it was around 1pm, I said the Evening Office, made easy by some app on my iPhone. The wonder of it all. Before entering I walked around the churchyard, reading such headstones as remained legible. I came across this one, and the text that clamoured for attention read "Gone but not forgotten". This is almost certainly no longer true. The person had been born in 1819 and had died in 1900. Remembered for a while, no doubt. But those doing the remembering - who knew the deceased - are themselves long dead. I read the inscription as a statement of hope and comfort, and of unexpressed fear. We shall all be 'forgotten'. I have long suspected that at the root of much human difficulty, evasion, maladaptation and anxiety is fear of our death and oblivion, our being forgotten. This is hardly ever faced (truly, hardly ever faced), and so we remain unaware of the cause but routinely suffer the consequences. Ernest Becker's The Denial of Death (1973) deals with this matter directly. It is a sobering but strangely liberating read. See the wiki summary here. Socrates advised that we practice dying (that is, face it, meditate upon it, live with its inevitability) in order to become morally serious (authentic) persons. "Human beings are mortal, and we know it. Our sense of vulnerability and mortality gives rise to a basic anxiety, even a terror, about our situation. So we devise all sorts of strategies to escape awareness of our mortality and vulnerability, as well as our anxious awareness of it. This psychological denial of death, Becker claims, is one of the most basic drives in individual behaviour, and is reflected throughout human culture. Indeed, one of the main functions of culture, according to Becker, is to help us successfully avoid awareness of our mortality. That suppression of awareness plays a crucial role in keeping people functioning – if we were constantly aware of our fragility, of the nothingness we are a split second away from at all times, we’d go nuts. And how does culture perform this crucial function? By making us feel certain that we, or realities we are part of, are permanent, invulnerable, eternal. And in Becker’s view, some of the personal and social consequences of this are disastrous." (Source: The Ernest Becker Foundation). Acquainting ourselves with the certainty of our death and our eventually being forgotten only enhances life. Its something we should practice.  We maybe chose the hottest time to visit Florence. I'm not built for heat. That aside, it was a memorable trip. A full two weeks allowed unhurried sightseeing, in Florence and beyond. We stayed in a flat at St Mark's English Church: no air-con, and 99 steps to reach it. The reward was this balcony (right) and its view of the church of Santo Spirito, designed by Brunelleschi and begun in 1428. Our days were bookended by it's bells. To my ear there is something wonderful about the slightly discordant and chaotic sound of continental church bells that makes English ringing sound like a corseted aunt. This church houses something that, of all the artefacts I saw on our trip, made the greatest impression: a crucifix believed to have been carved by a 17 year-old Michelangelo. The story is that he was allowed to make anatomical studies on the corpses coming from the convent's hospital; in exchange, he sculpted this which was placed over the high altar. It was thought to be lost, then resurfaced in the early 1960s, heavily overpainted. Today, cleaned up and restored, it hangs, suspended in mid-air in the octagonal sacristy off the west aisle of the church. I met Chris in 2005. We were attending a forum of Clerks and Directors of endowed London charities. We each found the occasion uninspiring, rather Dickensian in tone. We began our own group, just the two of us, and met every few months to discuss work, life, and the universe.

Chris held firm views and liked an argument. In the early days, I found this hard work. But we soon became friends, shared ideas about how our respective foundations might effectively help those who were held back by material poverty, and talked about much else besides. We were both Northerners and the same age, save for three weeks. We had both worked in local government, and each had some direct experience of the lack of opportunity we now sought to address for others through the foundations we worked for. I admired his thinking and focus, and his skill as an artist. His art, I pointed out to him, often addressed metaphysical matters that his rational mind liked to dismiss - themes such as identity, meaning, loss, heroism and sacrifice . He only half accepted that. He was more sensitive than he sometimes let on. His was a sharp and purposeful mind in a sector where sometimes sentimentality appears to reign. I valued that, and his friendship. His sudden death is a great loss. Below are images from his website (click images to enlarge). It is typical of his ironic approach to include his Chain Saw Proficiency certificate... |

|

|

(c) Hugh Valentine

|