For some years I have played with the idea of SSM (unpaid/volunteer) clergy and their stipendiary (paid clergy) friends meeting from time-to-time in the upper room of a pub where we might experiment with – learn to hold – conversations. The working title for this gathering was to be ‘Chapter & Verse’. It would be an Undergroud Seminary of sorts. There’d be none of the popular ‘theological expert’ speaker stuff followed by questions; instead we’d seek new ways of sharing knowledge, learning from one another, caring for one another, seeking God and reading the signs of the times. We’d aim to retake theology back from the academy and the ‘experts’ (or at least from its specialised annexation from our lived lives) and seek to learn afresh what it means to be stewards of the mysteries of God as Paul rather invitingly puts it [1 Cor 4:1].

|

A link to what I regarded as a valuable warning about some aspects of the Christian practice of spiritual direction has gone dead - the dreaded but common '404: page not found'. Luckily other copies exist of the article by the late Ken Leech and I have copied it below the line for those who are interested (follow 'read more'). I have always gently declined requests to become someone's spiritual director. It is not that I don't respect the function (I do). It is more that it can drift into an unhelpful compartmentalisation. I have, though, always been ready and very willing to meet and talk; to be the bearer of another's secrets and worries and an affirmer of their calling and value. An accompanist, not a director.

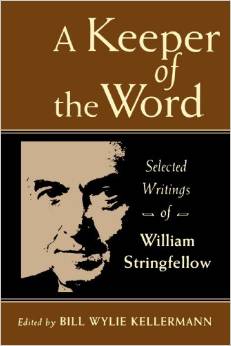

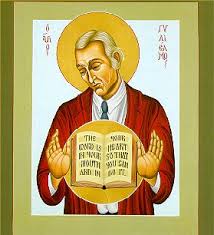

Discovering the writing of William Stringfellow some years ago was a memorable find. Here he is on "Career vs. Vocation"

“I had elected then [in my early student years] to pursue no career. To put it theologically, I died to the idea of career and to the whole typical array of mundane calculations, grandiose goals and appropriate schemes to reach them…. I do not say this haughtily; this was an aspect of my conversion to the gospel…. “[Later] my renunciation of ambition in favour of vocation became resolute; I suppose some would think, eccentric. When I began law studies, I consider that I had few, if any, romantic illusions about becoming a lawyer, and I most certainly did not indulge any fantasies that God had called me, by some specific instruction, to be an attorney or, for that matter, to be a member of any profession or any occupation. I had come to understand the meaning of vocation more simply and quite differently. “I believed then, as I do now, that I am called in the Word of God … to the vocation of being human, any work, including that of any profession, can be rendered a sacrament of that vocation. On the other hand, no profession, discipline or employment, as such, is a vocation.” A Keeper of the Word: Selected Writings of William Stringfellow (Eerdmans, 1994), pp. 30-31 |

|