I never knew him, and wish I had. John William Burke 1 March 1890 (born Shirebrook, Derbyshire) and died 24 June 1954 at Harworth (then Yorkshire, later Nottinghamshire). In my early life (I was born two years after his death) I was surrounded by miners and by the North Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire collieries. My recent research has reminded me of the terrible working lives miners endured, and the high risks to which they were routinely exposed. As a boy I was unaware of the demanding nature of their work. All I recall is that the miners living near us appeared to enjoy a good standard of living. This (I now see) reflected both the risks of the job and the power of their union - the NUM. Now, their existence and power are things of the past. In late 2012 the 540 employees at Maltby Main were given redundancy notices and its above-ground structures demolished in 2014. In our more aware age coal is a dirty fuel. Yet it made very many things possible. And those who worked down the mines deserve to be remembered.

|

I have been thinking about my maternal grandfather John William Burke. He was a pit worker in Yorkshire, a ‘deputy’, a kind of foreman. He worked at Maltby Main Colliery, one of the UK’s deep mines, noted for a major disaster on 28 July 1923 which killed 27 men and injured many more, my grandfather among them. I am told it affected his lungs. Eventually the condition shortened his life. Maltby Main closed for good in 2013. My grandfather is listed as one of the witnesses at the investigation by Sir Thomas Mottram (H M Chief Inspector of Mines) which resulted in the report “On the Causes of and Circumstances attending the Explosion which occurred at the Maltby Main Colliery, Yorkshire, On The 28th July, 1923”.

I never knew him, and wish I had. John William Burke 1 March 1890 (born Shirebrook, Derbyshire) and died 24 June 1954 at Harworth (then Yorkshire, later Nottinghamshire). In my early life (I was born two years after his death) I was surrounded by miners and by the North Nottinghamshire and South Yorkshire collieries. My recent research has reminded me of the terrible working lives miners endured, and the high risks to which they were routinely exposed. As a boy I was unaware of the demanding nature of their work. All I recall is that the miners living near us appeared to enjoy a good standard of living. This (I now see) reflected both the risks of the job and the power of their union - the NUM. Now, their existence and power are things of the past. In late 2012 the 540 employees at Maltby Main were given redundancy notices and its above-ground structures demolished in 2014. In our more aware age coal is a dirty fuel. Yet it made very many things possible. And those who worked down the mines deserve to be remembered.

0 Comments

"Get over yourself", when said to us by another, is often (usually) said as a rebuke, in anger, and is hurtful to hear. But the useful thrust of that perspective, when we can say it to ourselves, lovingly, is about the need to transcend our ego (something we all have). I found this helpful approach from Bertrand Russell: "Make your interests gradually become wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river — small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being." I met Chris in 2005. We were attending a forum of Clerks and Directors of endowed London charities. We each found the occasion uninspiring, rather Dickensian in tone. We began our own group, just the two of us, and met every few months to discuss work, life, and the universe.

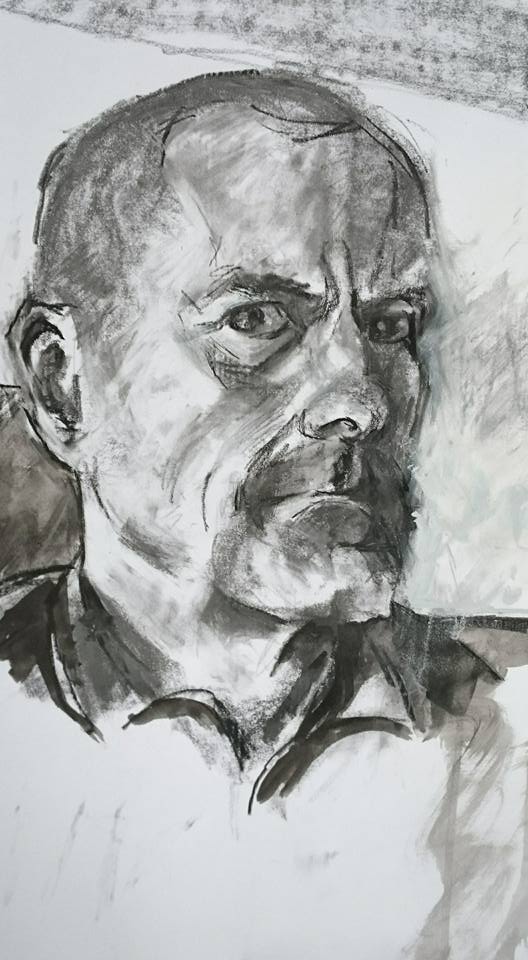

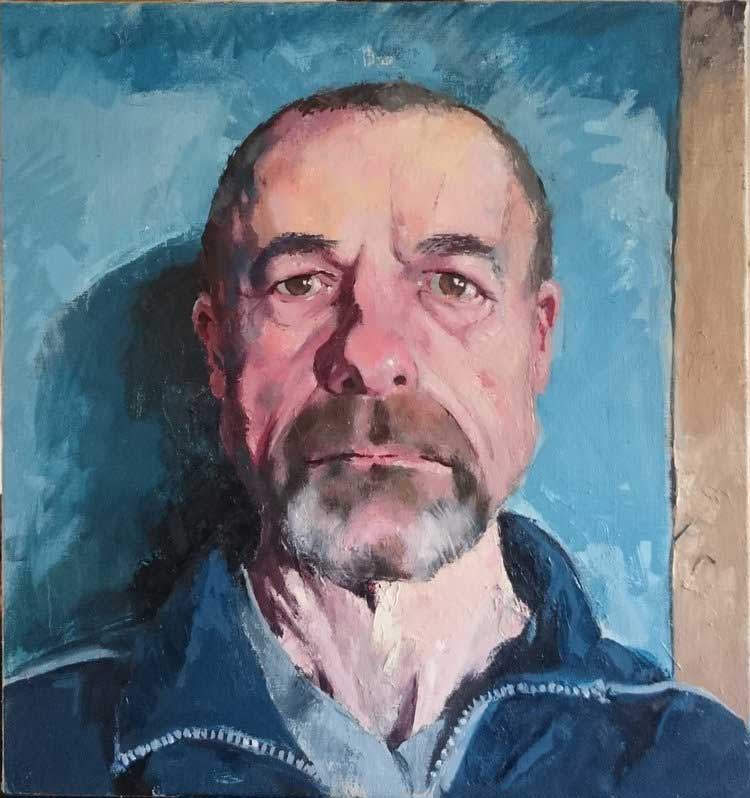

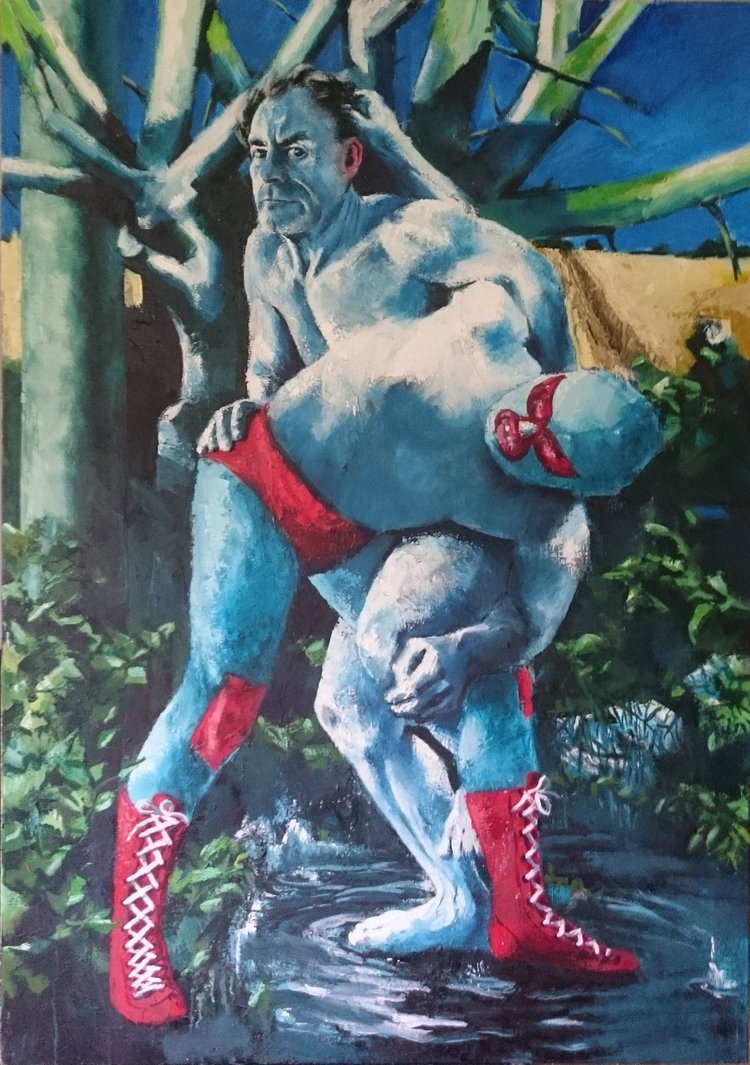

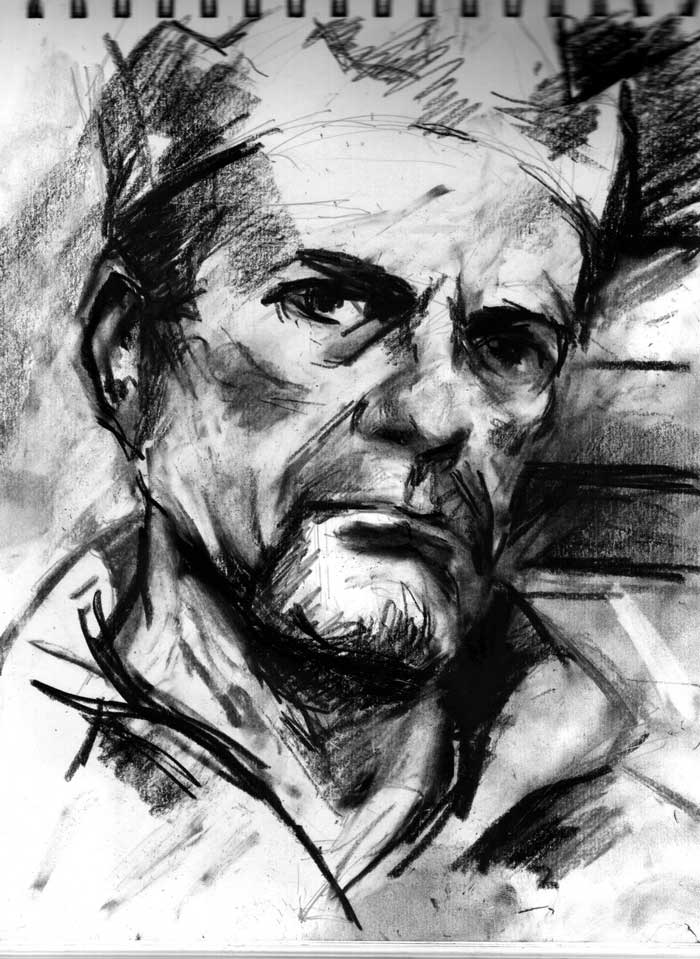

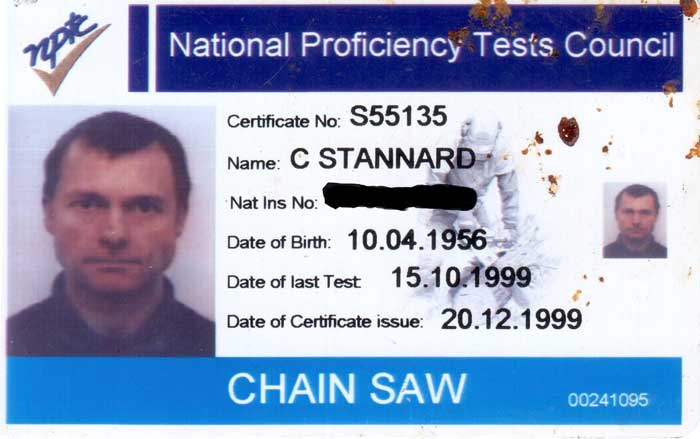

Chris held firm views and liked an argument. In the early days, I found this hard work. But we soon became friends, shared ideas about how our respective foundations might effectively help those who were held back by material poverty, and talked about much else besides. We were both Northerners and the same age, save for three weeks. We had both worked in local government, and each had some direct experience of the lack of opportunity we now sought to address for others through the foundations we worked for. I admired his thinking and focus, and his skill as an artist. His art, I pointed out to him, often addressed metaphysical matters that his rational mind liked to dismiss - themes such as identity, meaning, loss, heroism and sacrifice . He only half accepted that. He was more sensitive than he sometimes let on. His was a sharp and purposeful mind in a sector where sometimes sentimentality appears to reign. I valued that, and his friendship. His sudden death is a great loss. Below are images from his website (click images to enlarge). It is typical of his ironic approach to include his Chain Saw Proficiency certificate... I have always been suspicious of people who like to speak of their 'integrity'. I have observed how often this indicates something else, a rather overweening self-preoccupation. Treat these integrity-claimers with great caution. People of true integrity display that fact obliquely. They evidence it, rarely, if ever, claim it explicitly. They are to be trusted.

I am moved by this film about Herbert Fingarette, made by his grandson. Herbert worked as a philosopher and in one of his numerous books had concluded that the fear of death was irrational. Years later, the prospect of death began to frighten him. You can read the story here, in The Atlantic, and see the film, below. On watching it I wondered if perhaps the subject of his fear is in fact loss rather than death. And what a shining example of the film-maker's art: to observe and record and to let the story speak for itself.

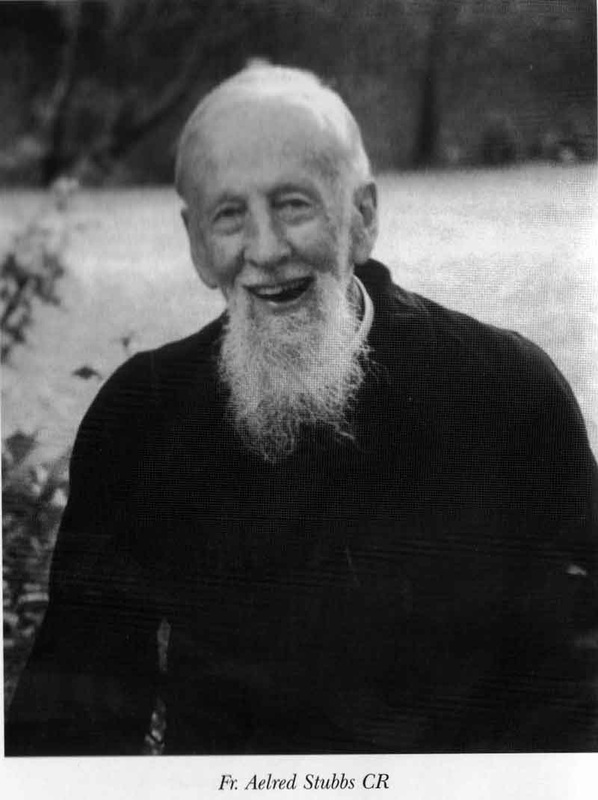

John died at the very end of 2017. He has been a friend and an inspiration. He is properly described as a worker-priest and he realised that unusual calling to a far greater extent than most of today's self-supporting priests. His experience of selling his labour (he worked for most of his life in Truman's Brewery on East London's Brick Lane) eventually made the church, as conventionally understood, a difficult environment in which to operate. This is an extract from a 2010 document John wrote, and recalls something of the tension he felt and the challenges he squared up to, as well as the clarity of his thought. "So my quarrel with the Church is not at the level of this evidently fascinating, but unproductive issue of "whether there is a God" or not. It is, rather, about the claim of the Christian religion to represent Jesus and the "values" and norms of the "Kingdom of God" which he embodied and served. This is not a new complaint. But, perhaps for any Christian such as myself, who has always wanted to know how to devote himself more genuinely, there's a natural "term" to the business of being committed to an association which, in effect, trivializes its own awesome objectives and speaks so relentlessly in a language nobody else can understand. In case anyone is interested (after all, someone reading this may well ask "What's the big deal? why all these words, only to arrive where so many of our contemporaries have long since ended up?) the question I feel obliged to face is: in the short time that remains to me, how am I to fulfil the obligation to Jesus and his "Kingdom of God" which I am unable to shake off despite my repudiation of the Church's theology? Certainly I cannot pretend that the Church has no value or never comes near to the Kingdom of God. The churches are often to be found doing, with a good will, the things which, as Jesus said, ought not to be left undone. Perhaps the same sort of claim could be made for the many movements of protest that are available. Should I not be content with the opportunities of the present times for political involvement? My natural commitment is to the anti-war, anti-nuclear (power as well as bomb), anti-imperialist movements. I share the widespread revulsion against what amounts to a Zionist hegemony in Palestine. There is no end to 'progressive' causes and to aspects of the campaign to deal adequately with global warming. These sorts of commitment were associated, in the past, with the socialist hope. Why should I not be wholehearted about one or more of them now? It may be because I have come to see that protest inevitably implies a sort of self-righteousness. Who can honestly face the dubiousness of his own self-interest – the possibility that there are grounds for surrendering the privileges and securities by which he makes himself irreproachable as an independent citizen? In fact, it is precisely as an "independent" citizen that I might, for example, come forward to protest that others should not lack the same sort of amenities as I enjoy. But, when it came to the crunch, how much would I allow my security to be threatened by the consequences of this kind of advocacy? So, knowing myself, I am not likely to abandon altogether either the Church or my favourite causes. However, I am on the lookout for some better way of (and some deeper reserve of courage for) affirming the Good News than "by word and sacrament", or by public demonstration - some authentic and unromantic way of joining those who, being society's rejects, are, unknown to themselves, the passport-holders of the Kingdom of God."  I was privileged to meet Bill - Father Bill as he was universally known - in 1987. I was on placement with him as part of my ordination training. We became friends. His priestly work was beyond the church-as-institution though firmly rooted in the church as a spiritual reality. He took the church seriously but was never a prisoner within its confines. He died in January 2018 after a dreadful ten years of suffering a psychotic illness compounded by dementia. He is probably best remembered - and loved - for his work with those living with and dying from AIDS, in Earls Court, London in the 1980s and 90s. His early training had been in nursing and the spiritual dimensions of care were very important to him. He accompanied and supported countless people as they approached death. It seems a terrible tragedy that his own decade-long illness of mind prevented him from being able to fully receive such support in his final years. His books included AIDS: Sharing the pain, Cry Love, Cry Hope and Going Forth: A practical and spiritual approach to dying and death. What a wonderful man. Father Bill Kirkpatrick; 16 June 1927 - 4 January 2018 Click 'read more' to see tribute I wonder very often at the pervasive presence of violence and violent impulses in our species. Think here less of outward and physical violence but of harmful intentions and responses and the myriad ways in which these permeate so much of human encounter: suspicion, gossip, denigration, undermining, sarcasm, blaming, cold-shouldering, false witness. What is the root of all this? I have long suspected that our species transmits violence, from generation to generation. If so, this explains its endurance and persistence. Perhaps it is a delusion, this idea many of us hold, that we are reasonable, rational and well-adjusted. What if we begin with another premise - that virtually all humans sustain harming traumas and experiences during our formative years, and that these remain at work in us, largely unconsciously, throughout our lives? In the more extreme cases, we see these - they are made manifest. But what if the situation I have described is endemic, and in most of us largely 'contained' (or so we might think) and so disguised? And what if we never find ourselves able to join up the dots - the 'standard' reactions we observe within us, the ways we conduct ourselves at work, in groups, how we handle intimacy, how we react to adversity and (often imagined) threat - and so remain unaware of enduring wounds which clamour for healing?

For the record, this has no connection, in my thinking, to so-called 'original sin' - a doctrine I cannot take seriously. But what if very many people suffer some kind of 'original harm' in their developmentally vital years, say from birth to early adulthood? Such events are vitually unavoidable, however loving our care givers: experiences of separation, of various forms of abandonment, of 'friendly' teasing or sarcasm, of rejection by other children in the way typical of other children. What if all these and more - things virtually inescapable in this world - leave negative imprints, things that shape us and remain alive as we move into adult life, even as (perhaps especially as) 'well adjusted', 'responsible', socially adept and outwardly 'successful' humans? Just a thought. I visited Macclesfield this week, a not-quite mid-way location for a meeting with a friend I see too little of. Virgin trains had whisked me there on time and in comfort and with clear and comprehensible in-train announcements, wondrously free of 'the next station stop will be...'. Next stations were - well, simply - the next station will be.. God bless them. And what a relief. But the company's thoughtfulness did not stop there. Whilst waiting for the 19:36 return train to London I gently walked the length of Platform 2, thinking. This must have sent the wrong signal because a uniformed voice from across the track enquired 'excuse me - are you all right?'. 'Yes, thank you', I said and went on to enquire in reply 'And how are you?' before realising that he had interpreted my mindful pacing and lost-in-thought-ness as signs of a possible railway suicide. Nothing had been further from my thoughts. Still, the enquiry seemed rather touching, and was far more welcome than, say, an unexpected rugby-tackle to the ground by zealous emergency service operatives. Maybe part of the distant look that worried him was when I caught sight of the Macclesfield supplier - visible from the platform and pictured below - which turned out to be a DIY shop.

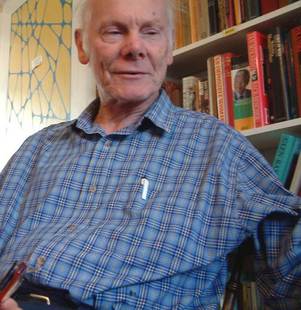

We met in a crypt of all places. In 1984 it still housed the Central London Samaritans and we were on the same evening shift. John lived in Stepney Green, at that time on my way home, so I started giving him lifts. I was soon invited to meet Lesley, and their daughter Alex (Libby was to arrive later). John and I became friends. And 33 years later his death makes the world feel empty to me. Meeting John in a crypt, a place of death, was paradoxical, for John turned out to be – for me and so many others – a bringer, a re-invigorator, of life. Like all the most valuable of people he is not easy to describe. Australian, but anglophile and with a strong sense that Scotland was home (he visited it as often as he could but couldn’t I think ever have lived there). A former alcoholic who became a therapist, and although with no formal qualifications was a tremendous healer of bruised hearts and minds. Both a misanthrope and a lover of people. Wry and penetrating in his observations of the world and its inhabitants and with persistent, self-deprecating humour. He ran courses on assertiveness (at one stage for the Bank of England no less). He could be withering and had no time for phoney people but for others the power and depth of his attention and care was transformative. When invited to any event involving more than two people he would, inexplicably, have a previous engagement. Like Kierkegaard, he sensed the untruth in many a crowd and formulaic exchange. As a boy he’d been beaten by Australian nuns and had no religious allegiance in adulthood, yet you’d be hard-pressed to find many others capable of such appreciative wonder and awe. “Have you been out yet? It’s the most magical day you ever saw in your life”. John was a disciple of gratitude. The ordinary could thrill him. He majored in childlike glee over a new sky, a discovered (or rediscovered) poem or insight, the tenor voice. We loved his oft-repeated line in self-mockery: “I know, I’m a great disappointment to myself”. I think, too, he knew fear, even despair. His body, he always insisted, was a temporary vehicle. He respected but did not sentimentalise or (heaven forbid) immortalise it. “My soul has its roots in the soil/It’s my calm belief/That I’m just a leaf, this thing called ME/And will fall from the tree”. For John the human ego was something to make fun of. “Poor little ego says/‘where shall ME go when I am dead?/I’m filled with dread”. He adopted the saying attributed to the Roman playwright Terence: I am human, and nothing of that which is human is alien to me. It summed up something central (and hard won) about John. Over these 33 years we have spoken to one another more or less at least every other day. Often the 'phoned exchanges were brief – a few minutes. But my, how I treasure the memory of them. Order of service from John's memorial gathering

I am nearly always inspired by Richard Holloway. I was struck by a particular recollection of his, found in this BBC Hardtalk interview at 4 minutes 22 seconds. He speaks of the shame he felt at having sent his hard-working labourer father a ‘pious’ letter urging him to embrace Jesus, RH remarks (with tears in his eyes) ‘religion gives you permission to perform these discourtesies’. Indeed it can. The whole interview is worth watching.

I visited the dentist today in Bermondsey and had to wait to check in whilst another patient was leaving and settling his bill at the desk. He was older - retired I should think. 'You've got my name wrong' he said to the receptionist after checking the print out. She apologised and went to correct it on the system. He inspected the result. 'Can I be pernickerty?' he asked, 'It should be The Reverend Doctor'

I am no longer surprised by the fondness I observe in fellow clergy for titles and honorifics, though it still disheartens me. We didn't enter the world with these baubles and they are not going to carry much weight when we depart - except possibly when too great an attachment to them harms our transition from life to death. In relation to the matter in hand, they bore no relevance to the state of his teeth. I had to chuckle as I found myself wondering if he would have be so keen on his indentifiers had we been in the queue not at the dentist but at the local sexual health clinic. Somehow I think not, but you never know. Yesterday, walking down Regent Street towards Piccadilly Circus, I spotted in my peripheral vision to the right a man who at first I thought had been taken ill. He looked pained, seemed to be losing his balance, as if some force had struck him. In the milliseconds it takes for us to absorb data, I noticed a woman a few yards away, who was obviously connected to him, and a possible storyline emerged. It seemed unambiguously the case that she had delivered some words to him, and the effect dealt him a mortal blow. 'I've met someone' maybe. Or 'I don't love you anymore'. Or 'I want to end it'. I hope I was mistaken, but I think not. They were in their twenties I should reckon; the age where love affairs seem inescapably tempestuous and sometimes a little violent. The hot and coldness of it all, the testing and the provocations. I felt deeply for him.

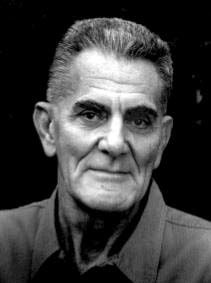

I knew John in the early 1980s in Bradford. I was at the university and John was a friend of some of my friends. I liked him. He was gruff, the way male Northerners could be – and can be still. There was also, I picked up, a sensitivity there. I forget how many times we met though I remember we had some good conversations and I seem to recall one walk with mutual friends ending up at his West Yorkshire cottage. We lost touch when I moved to London, as I lost touch with other people in that circle: Andy, Sue, Julia, Rose, Paul. Some years ago I heard that he had become a counsellor in Keighley, and easily tracked him down via the internet and we exchanged a couple of friendly emails. In a recent telephone call to one of that group – Rose – I heard that John had died just a month before. He was in his early sixties. Another search found his website and a reference to a book he had written about both his illness and his work. I ordered it, and have just read it. Fields of Freedom: Breaking through fear in personal and professional life. Whether correctly attributed to Socrates, the claim that the ‘unexamined life is not worth living’ rings true for many of us. I also value John Ruskin’s claim that ‘The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way’. John’s adult life and his book – testament is the right description – pay honour to both these insights. Early experiences of humiliation (father, school teachers, another boy) left their mark. As an adult his response to these appears fundamentally creative: professional work first with wayward youngsters, then becoming a counsellor and therapist. His book records a near constant interest in ‘personal development', taking in group encounter (some with the men’s movement) and a good deal of study of various schools of thought and practice from radionic healing to transactional analysis. The book was written with death on the horizon. It is a worthy testament to a life lived with the intention of turning trauma and hurt into a life authentically lived in the service of others. John, I am so sorry that life was cut short. I am not good company in art galleries. The majority of pictures do not impress or detain me. I have no interest in chit chat about the exhibits. But from time to time a work or image stops me in my tracks. This was one such, encountered last week in the new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The Subway (1950) by George Tooker. I did not know of the artist and have since enjoyed discovering more. It is said that he responded to and portrayed modern day alienation and anxiety. He does it brilliantly, and menacingly. He died aged 90 in 2011.

|

|