I was privileged to meet Bill - Father Bill as he was universally known - in 1987. I was on placement with him as part of my ordination training. We became friends. His priestly work was beyond the church-as-institution though firmly rooted in the church as a spiritual reality. He took the church seriously but was never a prisoner within its confines. He died in January 2018 after a dreadful ten years of suffering a psychotic illness compounded by dementia.

He is probably best remembered - and loved - for his work with those living with and dying from AIDS, in Earls Court, London in the 1980s and 90s. His early training had been in nursing and the spiritual dimensions of care were very important to him. He accompanied and supported countless people as they approached death. It seems a terrible tragedy that his own decade-long illness of mind prevented him from being able to fully receive such support in his final years. His books included AIDS: Sharing the pain, Cry Love, Cry Hope and Going Forth: A practical and spiritual approach to dying and death. What a wonderful man.

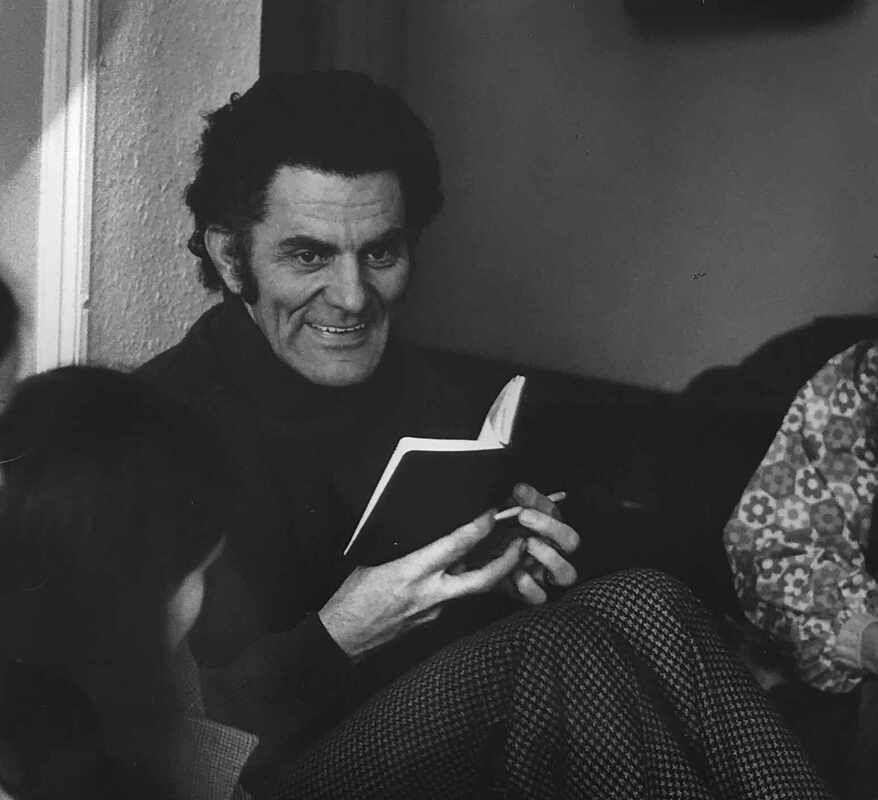

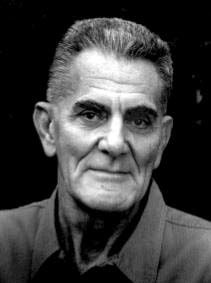

Father Bill Kirkpatrick; 16 June 1927 - 4 January 2018

Click 'read more' to see tribute

He is probably best remembered - and loved - for his work with those living with and dying from AIDS, in Earls Court, London in the 1980s and 90s. His early training had been in nursing and the spiritual dimensions of care were very important to him. He accompanied and supported countless people as they approached death. It seems a terrible tragedy that his own decade-long illness of mind prevented him from being able to fully receive such support in his final years. His books included AIDS: Sharing the pain, Cry Love, Cry Hope and Going Forth: A practical and spiritual approach to dying and death. What a wonderful man.

Father Bill Kirkpatrick; 16 June 1927 - 4 January 2018

Click 'read more' to see tribute

TRIBUTE TO THE REVD BILL KIRKPATRICK

At his Requiem Mass/Funeral Monday 29 January 2018

St Cuthbert’s Philbeach Gardens Earl’s Court London

(There were two tributes, followed by a sermon)

We attend funerals out of love or duty. And tributes to dead clergy often major on outward achievement: a succession of church roles, the gathering of longer ecclesiastical titles and honorifics. I believe most of us here are here because of love. And Bill chose a path that took him far away from the church’s rewards radar.

I first met him as the result of a deception, of sorts. I was on the Southwark Ordination Course and was required to find a placement. We were to choose a setting quite different to one we might feel naturally at ease in, and the Principal thought I should find some evangelical parish to spend time with. I managed to make the case that I had had extensive experience of the evangelical approach to Christian faith, though I concealed the fact that it had been painfully negative and had left me hurt and angry.

I was then working as a social worker in Bermondsey and was set on the path of wanting to become a worker-priest. I reported having heard of Bill Kirkpatrick and his particular approach to that vocation. The proposal was approved, and I dropped Bill a letter.

He suggested a preliminary meeting before saying yes. I arrived at his Earl’s Court basement flat to encounter – as many of you will have encountered – a man who was unusually ‘present’ without in any way being intimidating; who seemed to inhabit an interior silence without in any way being inaccessible; who approached listening as something significantly more than keeping silent whilst another spoke.

That was around 1987. It was a time of fear amongst gay men, and in society at large, about AIDS. Attitudes in the Church, especially towards gay clergy, hardened with a dreadful debate in Synod that year.

Against this spreading chill Bill kept his nerve and his courage and helped many of us survive those dark days. His own discipline meant that he was not himself paralysed by these things. He would explain that he took them to God in prayer – the kind of traditional formulation that can so easily be a religious cliché and an evasion, but never was so with him.

Bill had experienced trauma in his early years. He described himself as a ‘lovechild’ but realised that his conception probably had little to do with love and soon led to his abandonment . As he put it: “within a month of my birth I was shipped off to a private orphanage”.

Insecurities in childhood’s crucially developmental years exact a high price. And growing up gay in a straight world, likewise. Bill’s early experiences were ones which left him with the messages that he did not fully belong, was not fully wanted, was not really approved of.

What he managed to achieve in the light of those messages has been astonishing. His life provides an infinitely more compelling reading of Christ’s Gospel than any barrow-load of academic theology or traditional preaching or church pronouncements.

Bill brought himself, without adornment, to the energy the Church calls grace and the results have been significant and beautiful. In the most straightforward of ways he contemplated what the gospels say about the elusive Nazarene and he sought to live that out in the costly way of giving himself to others. ‘Listening’ and ‘being there’ go a good way towards summing up Bill’s life and work, but only if heard beyond the language of cliché. The transformation of our psychic wounds into the unself-conscious business of loving and healing others is indeed the work of grace. And in this, Bill’s life and witness has been, remains, of tremendous significance.

The aspect of his work for the Gospel which meant and means so much to me is the way he modelled priestly work beyond the walls of the institution. To welcome outsiders into church is one thing (and a valuable and necessary thing to be sure); to be the church beyond those walls and amongst those not valued by the church (however much that is disguised by Christian double-speak) is another. And Bill did it.

I mentioned childhood trauma and Bill’s experience of it. And we, his friends – his family of friends – have also experienced a kind of trauma over this past decade in seeing all that has so wonderfully and powerfully epitomised this beautiful man taken away by a disease of the mind. This feels like a long delayed funeral. It is a very old problem for Christian people that the extent of human suffering challenges claims about God, but mostly we find a way of making some residual sense of these conflicting realties; yet there are times when it becomes very hard indeed, and Bill’s last decade has caused many of us distress and sorrow.

But, that has now ended. What remains is the shining example of someone who, from his own experience of being wounded, helped heal others.

Bill: how we loved you, how we have missed you, and miss you. Against the distressing messages you heard as a young man, hear this: you have been a truly fine priest and an exemplary human being.

Hugh Valentine

At his Requiem Mass/Funeral Monday 29 January 2018

St Cuthbert’s Philbeach Gardens Earl’s Court London

(There were two tributes, followed by a sermon)

We attend funerals out of love or duty. And tributes to dead clergy often major on outward achievement: a succession of church roles, the gathering of longer ecclesiastical titles and honorifics. I believe most of us here are here because of love. And Bill chose a path that took him far away from the church’s rewards radar.

I first met him as the result of a deception, of sorts. I was on the Southwark Ordination Course and was required to find a placement. We were to choose a setting quite different to one we might feel naturally at ease in, and the Principal thought I should find some evangelical parish to spend time with. I managed to make the case that I had had extensive experience of the evangelical approach to Christian faith, though I concealed the fact that it had been painfully negative and had left me hurt and angry.

I was then working as a social worker in Bermondsey and was set on the path of wanting to become a worker-priest. I reported having heard of Bill Kirkpatrick and his particular approach to that vocation. The proposal was approved, and I dropped Bill a letter.

He suggested a preliminary meeting before saying yes. I arrived at his Earl’s Court basement flat to encounter – as many of you will have encountered – a man who was unusually ‘present’ without in any way being intimidating; who seemed to inhabit an interior silence without in any way being inaccessible; who approached listening as something significantly more than keeping silent whilst another spoke.

That was around 1987. It was a time of fear amongst gay men, and in society at large, about AIDS. Attitudes in the Church, especially towards gay clergy, hardened with a dreadful debate in Synod that year.

Against this spreading chill Bill kept his nerve and his courage and helped many of us survive those dark days. His own discipline meant that he was not himself paralysed by these things. He would explain that he took them to God in prayer – the kind of traditional formulation that can so easily be a religious cliché and an evasion, but never was so with him.

Bill had experienced trauma in his early years. He described himself as a ‘lovechild’ but realised that his conception probably had little to do with love and soon led to his abandonment . As he put it: “within a month of my birth I was shipped off to a private orphanage”.

Insecurities in childhood’s crucially developmental years exact a high price. And growing up gay in a straight world, likewise. Bill’s early experiences were ones which left him with the messages that he did not fully belong, was not fully wanted, was not really approved of.

What he managed to achieve in the light of those messages has been astonishing. His life provides an infinitely more compelling reading of Christ’s Gospel than any barrow-load of academic theology or traditional preaching or church pronouncements.

Bill brought himself, without adornment, to the energy the Church calls grace and the results have been significant and beautiful. In the most straightforward of ways he contemplated what the gospels say about the elusive Nazarene and he sought to live that out in the costly way of giving himself to others. ‘Listening’ and ‘being there’ go a good way towards summing up Bill’s life and work, but only if heard beyond the language of cliché. The transformation of our psychic wounds into the unself-conscious business of loving and healing others is indeed the work of grace. And in this, Bill’s life and witness has been, remains, of tremendous significance.

The aspect of his work for the Gospel which meant and means so much to me is the way he modelled priestly work beyond the walls of the institution. To welcome outsiders into church is one thing (and a valuable and necessary thing to be sure); to be the church beyond those walls and amongst those not valued by the church (however much that is disguised by Christian double-speak) is another. And Bill did it.

I mentioned childhood trauma and Bill’s experience of it. And we, his friends – his family of friends – have also experienced a kind of trauma over this past decade in seeing all that has so wonderfully and powerfully epitomised this beautiful man taken away by a disease of the mind. This feels like a long delayed funeral. It is a very old problem for Christian people that the extent of human suffering challenges claims about God, but mostly we find a way of making some residual sense of these conflicting realties; yet there are times when it becomes very hard indeed, and Bill’s last decade has caused many of us distress and sorrow.

But, that has now ended. What remains is the shining example of someone who, from his own experience of being wounded, helped heal others.

Bill: how we loved you, how we have missed you, and miss you. Against the distressing messages you heard as a young man, hear this: you have been a truly fine priest and an exemplary human being.

Hugh Valentine