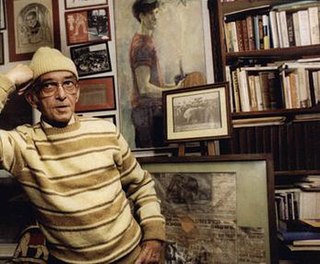

William Stringfellow: no distant prophet

|

I discovered accounts of, and later the writings of, William Stringfellow, rather late in the day. Somehow I had never heard of him - not in discussion, sermons or my theological education. I post this brief summary in the hope that others might also encounter him.

William Stringfellow (1928 - 1985) was born in Johnston, Rhode Island USA. His family not well off. But he was clever, and obtained scholarships which paid for college and, later, a spell at the London School of Economics. After service in the US Army he attended Harvard Law School, and after his graduation, moved to a slum tenement in Harlem, New York City to work as a lawyer among poor African-Americans and Hispanics. He was a lifelong Anglican (Episcopalian as they say in the USA). He was a prolific writer, though most of his books fell off the publisher’s lists after he died (of diabetes in 1985). In summary –

Some of what he says to me:

Works A Public and Private Faith, 1962 Instead of Death, 1963 My People Is the Enemy, 1964 Free in Obedience, 1964 Dissenter in a Great Society, 1966 (with Anthony Towne) The Bishop Pike Affair, 1967 Count It All Joy, 1967 Imposters of God: Inquiries into Favourite Idols, 1969 A Second Birthday, 1970 Suspect Tenderness: The Ethics of the Berrigan Witness, 1971 An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land, 1973 (with Anthony Towne) The Death and Life of Bishop Pike, 1976 Instead of Death, 1976 Conscience and Obedience, 1977 A Simplicity of Faith: My Experience in Mourning, 1982 The Politics of Spirituality, 1984 William Stringfellow: career vs. vocation |

“William Stringfellow’s theological writing is pervaded by the conviction that the resurrection of Jesus frees us from the dominion of death. The world is ruled by principalities – by suprahuman, suprapersonal institutional powers which bind human life to the service of death. But the gospel sets us free to live and work within these institutions as servants of Christ; we are freed from the dominion of the principalities, since the resurrection of Christ frees us from the fear of death. Since death is the only power with which the principalities can threaten us, we have nothing whatsoever to fear! This, for Stringfellow, is the gospel; this is the Christian life. “ |