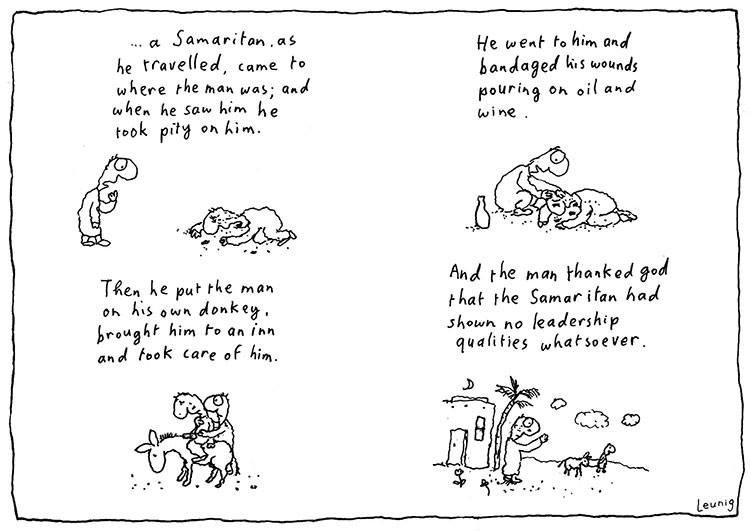

Have you noticed how, in recent years, an obsession with 'leadership' and 'leaders' has crept into much discourse (and fantasy) about business, the third sector, the public sector and even the churches? It's a great bore. Organisations need competent managers at every level, and those in such roles will, inevitably and necessarily, influence, shape and 'lead' developments in those organisations. But what seems to have happened is that this essential function and aspect has now become personalised into 'a leader'. This is ego-talk. Many find it irresistible.

In the church (I am mostly familiar with the Church of England) the 'leadership' fetish has grown apace. A small example is the growing number of church websites that now list the clergy as 'the leadership team' - and I have seen some that locate them in 'the senior leadership team'. Frankly, it's all so desperate. What should be fellowship often seems now to be follower-ship.

To have leaders, you need the led. There is a place for this where it is operationally and functionally necessary for tightly defined outcomes (think uniformed services and organisations with precise functions and outcomes). But in Christian communities it can only produce drone-disciples who surrender responsibility for their own Christian life to the 'experts', the leaders. And don't think that the ghastly cliché about 'servant-leader' avoids the pitfalls and dangers.

I recently attended a mandatory safeguarding course, attended mostly by clergy and with some churchwardens. The (very competent) facilitator had, as part of her input, referred to the role that power and power-imbalances play in church abuse, and had illustrated this by some high-profile cases. As the event progressed, I was struck by how often 'leader' and 'leadership' were used by participants - in a sometimes slightly self-aggrandising way ("As the leader of my parish..."). I pointed this out, this link with what we had been told and how the conversation was going. There was some agreement, but others thought the two things were quite separate.

Mainline church denominations 'embody' power relations and differentials in various ways, some subtle. Priests and bishops over laity, for example. Church architecture is another (the sacred sanctuary and altar, with the laity in their theatre-like pews). And another is found in who may speak and who is required to 'reply' following a set script. These are aspects of liturgical exchanges and liturgical life.

I set these matters out bluntly to illustrate dimensions we often don't see clearly. There are many clergy who operate within these structures with attentiveness, humanity and sensitivity, and who mitigate the more dangerous aspects of the leadership fetish. They focus, first, on being disciples. But there are some clergy who don't. And there are laity who like to be 'led'. That does not make for mature Christian explorers.

In the church (I am mostly familiar with the Church of England) the 'leadership' fetish has grown apace. A small example is the growing number of church websites that now list the clergy as 'the leadership team' - and I have seen some that locate them in 'the senior leadership team'. Frankly, it's all so desperate. What should be fellowship often seems now to be follower-ship.

To have leaders, you need the led. There is a place for this where it is operationally and functionally necessary for tightly defined outcomes (think uniformed services and organisations with precise functions and outcomes). But in Christian communities it can only produce drone-disciples who surrender responsibility for their own Christian life to the 'experts', the leaders. And don't think that the ghastly cliché about 'servant-leader' avoids the pitfalls and dangers.

I recently attended a mandatory safeguarding course, attended mostly by clergy and with some churchwardens. The (very competent) facilitator had, as part of her input, referred to the role that power and power-imbalances play in church abuse, and had illustrated this by some high-profile cases. As the event progressed, I was struck by how often 'leader' and 'leadership' were used by participants - in a sometimes slightly self-aggrandising way ("As the leader of my parish..."). I pointed this out, this link with what we had been told and how the conversation was going. There was some agreement, but others thought the two things were quite separate.

Mainline church denominations 'embody' power relations and differentials in various ways, some subtle. Priests and bishops over laity, for example. Church architecture is another (the sacred sanctuary and altar, with the laity in their theatre-like pews). And another is found in who may speak and who is required to 'reply' following a set script. These are aspects of liturgical exchanges and liturgical life.

I set these matters out bluntly to illustrate dimensions we often don't see clearly. There are many clergy who operate within these structures with attentiveness, humanity and sensitivity, and who mitigate the more dangerous aspects of the leadership fetish. They focus, first, on being disciples. But there are some clergy who don't. And there are laity who like to be 'led'. That does not make for mature Christian explorers.