St George in the East, London, E1

The history of the Church of England in London's East End is rich and fascinating. This page directs you to a valuable archive about one parish, that of St George in the East, Canon Street Road, London E1. It appears to be an archived collection of pages. My fear is that at some point it will disappear (web pages and domains do). My efforts to contact the web person have gone unanswered. For the moment, the site may be accessed here. I plan to copy its content and post it below when time allows. This will be in appreciation, not theft.

History of the parish & its principal church

Anglican churches or parishes founded by St George-in-the-East

Two further parishes were later incorporated into St George's parish (and the boundary with St Peter London Dock was adjusted in 1989, transferring the St Katharine's Dock area to St Peter's):

Former Anglican parishes which are part of the present-day parish

In the 17th and 18th century dissenters, and churches serving foreign nationals, were rather more active locally than the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church. By the middle of the 19th century that had changed; in answer to the question posed in 1851 Are there may Dissenters in your parish? Bryan King observed (though how accurately?) There are not many DIssenters; in fact, the people are too poor to support either Dissenters or any teachers without extraneous aid. However, there had been a huge variety of such places of worship in the parish, chronicled here:

(former) churches of other denominations

There are also pages about the history and growth of various areas of the present-day parish (some of them previously in adjacent, now merged, parishes):

The first-ever nationwide census of religious attendance was conducted on Mothering Sunday 1851; here are the figures for the borough of Tower Hamlets, with some comments. In 1859 there were 467 marriages in the registration district of St George-in-the-East: 281 in the Church of England, 172 Roman Catholic, 7 in other Christian churches and 7 under the auspices of the Superintendent Registrar [i.e. civil ceremonies].

Ritualism Riots, 1859-60

The one thing many people know about St George-in-the-East is that there were riots in church over matters of ritual and ceremonial. It is an extraordinary tale, which has been extensively written about; you can find a summary here. We marked their 150th anniversary with a programme of special events, including a visit by the Archbishop of Centerbury.

Parish worship after 1860

After the riots, things calmed down. Ironically, since those days worship at St George's has been of a 'central' character, alongside our high and low church neighbours! The pattern of Sunday worship in 1863, according to a somewhat cursory (and perhaps incomplete) Guide to the Church Services in London and its suburbs, was 11am (HC on the first Sunday), 3.30pm and 7pm, with a weekday service on Tuesday at 7pm. By 1875 - when Harry Jones had been Rector for two years - it was as follows (see also Dickens' Directory of London for 1879):

Services Sunday HC 8.00, 1st S and greater festivals, 11.45, M 11.00, E with churchings 3.00, E with baptism 4.15, E 7.00; Daily, M 11.00; Festivals M 11.00, HC am. Choir, partly paid. Music, Anglican. Surplice in pulpit. Seats 1200, all free. Offertory, at each service.

Weekday Matins at 11am was a pattern in other parishes at this period - and often well-attended. Note the inclusion of 'surplice in pulpit', in the light of the Ritualism Riots. Seats...all free; offertory shows that the parish had managed to abolish pew rents, and took collections. See here for the evidence presented by the Rev G.H. McGill of Christ Church Watney Street (on behalf of Stepney deanery clergy) to the Select Committee on the Ecclesiastical Commission in 1862, which gives detailed facts and figures showing how hard it was to sustain parish finances with uncollectable pew rents, practically no help from local businesses, and limited or non-existent endowments in the new district churches; and here for the case made by Harry Jones in 1875 against the creation of district churches, for a variety of reasons, including financial.

Schools

A major change in education provision came with the 1870 Education Act - see here for details of its impact locally, and of all the Board Schools that were built in the parish and their subsequent fate.

Church and community

The parish workhouse and infirmary, and the poor law schools, loomed large in the local consciousness. Here and here are the two parts of an 1866 newspaper article describing the experience of a 'female casual' in the workhouse. Charles Dickens, in chapter 3 of The Uncommercial Traveller (a collection of his sketches about various parts of London) describes in graphic detail a visit to Wapping Workhouse - passing en route 'Mr Baker's trap', a site of many suicides named after the local coroner; it makes grim reading, but he concludes that the workhouse was an establishment highly creditable to those parts, and thoroughly well administered by a most intelligent master. He called for an equalisation of Poor Law rates across London, finding it absurd that the poorest districts had to find the highest rates: 5s.6d. in the pound in one East End parish, as against 7d. in the pound in St George Hanover Square!

By 1870, for the first time, the district was classed as one of the five poorest in London. But the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians - like their counterparts in Stepney and Whitechapel - virtually ceased making 'out-relief' payments (as opposed to 'in-relief' - the workhouses). This was partly because of the growing influence of the Charity Organisation Society which pressed for more targeted assistance.

- Trinity Episcopal Chapel 1831-??

- Christ Church Watney Street 1841-1951

- St Mary Johnson Street (Cable Street) 1850 - [now a separate parish, officially but confusingly still called 'St Mary, St George-in-the-East']

- the Chapel of St Saviour & St Cross (1857-68), previously the Danish Church (1692-1824) - see below - which then became part of....

- St Peter London Dock 1866- [now a separate parish]

- St Matthew Pell Street 1848-1891, taken over from the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion - see below

- St John the Evangelist-in-the-East Grove Street [now Golding Street] 1869-1943

Two further parishes were later incorporated into St George's parish (and the boundary with St Peter London Dock was adjusted in 1989, transferring the St Katharine's Dock area to St Peter's):

Former Anglican parishes which are part of the present-day parish

- St Mark Whitechapel 1839-1925 (with a mission chapel of St Clement from 1866-??); on closure St Mark's was joined to....

- St Paul's Church for Seamen, Dock Street 1847-1971, which was a replacement for the Episcopal Floating Church 1825-45

In the 17th and 18th century dissenters, and churches serving foreign nationals, were rather more active locally than the Church of England or the Roman Catholic Church. By the middle of the 19th century that had changed; in answer to the question posed in 1851 Are there may Dissenters in your parish? Bryan King observed (though how accurately?) There are not many DIssenters; in fact, the people are too poor to support either Dissenters or any teachers without extraneous aid. However, there had been a huge variety of such places of worship in the parish, chronicled here:

(former) churches of other denominations

- Danish Church (1692-1824), Wellclose Square - which then housed a succession of nondenominational mariners missions and then became St Saviour & St Cross Mission Chapel - see above

- Swedish Church (1729-1911), Swedenborg Gardens

- German churches: St George's Lutheran Church (1763- ), Alie Street - now the home of the Historic Chapels Trust; St Paul's Reformed Church (1696-1941), Hooper Street; German Wesleyan Church

- various Baptist chapels

- various Independent / Presbyterian / Congregationalist chapels

- Methodist chapels, including St George's Wesleyan Church whose burial ground is now part of St George's Gardens, and the Countess of Huntingdon's chapel (see above)

- Roman Catholic churches

- other non-denominational missions and projects

There are also pages about the history and growth of various areas of the present-day parish (some of them previously in adjacent, now merged, parishes):

- Precinct of Wellclose, once a Liberty of the Tower of London, and Wellclose Square, a centre of 'liberty'

- Goodman's Fields - theatres, Prescot Street, Leman Street

- Magdalen Hospital for the reception of Penitent Prostitutes

- East Smithfield, including the Royal Mint

- Ratcliff Highway, including the famous murders of 1811-12

- Cable Street from earliest times to the present day

- Rosemary Lane and Rag Fair

- Backchurch Lane and Pinchin Street

- St John's parish

- Cannon Street Road and Ponler Street

- Sugar Refining; Wool and Tobacco warehouses

- housing - Peabody Estate, Katharine Buildings, and for a much later period St George's Estate

- Hessel Street - a centre of Jewish life

- Synagogues throughout the parish, reflecting the steady growth of its Jewish population

- Watney Street

- Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] area

- Schools in the parish

- Workhouse and Infirmary

- The Fortunes of the clergy - an explanation of the history of stipends and the struggle to make ends meet

- Churchwardens and their families - 18th century and 19th century

The first-ever nationwide census of religious attendance was conducted on Mothering Sunday 1851; here are the figures for the borough of Tower Hamlets, with some comments. In 1859 there were 467 marriages in the registration district of St George-in-the-East: 281 in the Church of England, 172 Roman Catholic, 7 in other Christian churches and 7 under the auspices of the Superintendent Registrar [i.e. civil ceremonies].

Ritualism Riots, 1859-60

The one thing many people know about St George-in-the-East is that there were riots in church over matters of ritual and ceremonial. It is an extraordinary tale, which has been extensively written about; you can find a summary here. We marked their 150th anniversary with a programme of special events, including a visit by the Archbishop of Centerbury.

Parish worship after 1860

After the riots, things calmed down. Ironically, since those days worship at St George's has been of a 'central' character, alongside our high and low church neighbours! The pattern of Sunday worship in 1863, according to a somewhat cursory (and perhaps incomplete) Guide to the Church Services in London and its suburbs, was 11am (HC on the first Sunday), 3.30pm and 7pm, with a weekday service on Tuesday at 7pm. By 1875 - when Harry Jones had been Rector for two years - it was as follows (see also Dickens' Directory of London for 1879):

Services Sunday HC 8.00, 1st S and greater festivals, 11.45, M 11.00, E with churchings 3.00, E with baptism 4.15, E 7.00; Daily, M 11.00; Festivals M 11.00, HC am. Choir, partly paid. Music, Anglican. Surplice in pulpit. Seats 1200, all free. Offertory, at each service.

Weekday Matins at 11am was a pattern in other parishes at this period - and often well-attended. Note the inclusion of 'surplice in pulpit', in the light of the Ritualism Riots. Seats...all free; offertory shows that the parish had managed to abolish pew rents, and took collections. See here for the evidence presented by the Rev G.H. McGill of Christ Church Watney Street (on behalf of Stepney deanery clergy) to the Select Committee on the Ecclesiastical Commission in 1862, which gives detailed facts and figures showing how hard it was to sustain parish finances with uncollectable pew rents, practically no help from local businesses, and limited or non-existent endowments in the new district churches; and here for the case made by Harry Jones in 1875 against the creation of district churches, for a variety of reasons, including financial.

Schools

A major change in education provision came with the 1870 Education Act - see here for details of its impact locally, and of all the Board Schools that were built in the parish and their subsequent fate.

Church and community

The parish workhouse and infirmary, and the poor law schools, loomed large in the local consciousness. Here and here are the two parts of an 1866 newspaper article describing the experience of a 'female casual' in the workhouse. Charles Dickens, in chapter 3 of The Uncommercial Traveller (a collection of his sketches about various parts of London) describes in graphic detail a visit to Wapping Workhouse - passing en route 'Mr Baker's trap', a site of many suicides named after the local coroner; it makes grim reading, but he concludes that the workhouse was an establishment highly creditable to those parts, and thoroughly well administered by a most intelligent master. He called for an equalisation of Poor Law rates across London, finding it absurd that the poorest districts had to find the highest rates: 5s.6d. in the pound in one East End parish, as against 7d. in the pound in St George Hanover Square!

By 1870, for the first time, the district was classed as one of the five poorest in London. But the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians - like their counterparts in Stepney and Whitechapel - virtually ceased making 'out-relief' payments (as opposed to 'in-relief' - the workhouses). This was partly because of the growing influence of the Charity Organisation Society which pressed for more targeted assistance.

Licensed Workers (Accredited Lay Workers) St George in the East London E1

Over the years many women have served the churches of the parish as full-time workers with skill and devotion. As the following notes show, some came from 'grand' families, drawn to service in the East End like those who joined the emergent religious communities for women. Over time, their commitment to the area was informed by rigorous training (more so than that of their male counterparts): some would doubtless have been accepted for ordained ministry if this had been possible in their time. Here are accounts of some of them.

Emily FitzHardinge Berkeley

Miss Berkeley was born in Agra, India in 1862. She was a member of a titled family, a relative of the Hon Fitzhardinge Berkely MP, whose son appears in lists of prominent converts to Roman Catholicism. She lived in the Rectory, working in the parish until about 1920. In November 1924 the Rector wrote "Miss Emily FitzHardinge Berkeley will be remembered by many readers of this magazine, although failing health brought her active work in the parish to an end four years ago. She was a considerable sufferer but managed to keep in touch with many of her old friends till the end. When able to go out, she has attended St. Paul's, Shadwell, finding the steps up to St. George's a serious matter owing to her weak heart. She was a most Devoted worker, always willing to spend herself and all she has for Christ, but never, if she could help it, a penny upon herself. Her example will long live with us."

Phyllis Hatton (1919-25)

Phyllis Hatton worked in the parish in the early 1920s, living in the Rectory. When the Revd J C Pringle came as Rector after the War, congregational numbers were low and the Bishop would not authorise a curate, preferring to appoint 'women workers' to organise the pastoral work. Miss Hatton was primarily involved with committee work, in a style which the Rector, himself committed to this approach, no doubt approved despite his regret at being denied a clerical colleague. Her work with the clubs and societies of the parish was an 'extra', and suggests she was a workaholic (she had some periods of stress-related absence). His farewell tribute in the April 1925 magazine - he left at the same time, the reason for her being moved to diocesan work - hints at this:

"Miss P.M. Hatton has left us after 5½ years of most strenuous service in the parish. The Diocesan Board of Women's Work announced that for two years they have regarded her as just the person for their work, and that they had thought this a good opportunity of securing her services. She entered upon her duties at the London Diocesan House, 33 Bedford Square, at the beginning of March. She has our best wishes for her health and strength and success in her new work. Miss Hatton was specially approved by the Bishop of Stepney for the task of organising the Social Service of this parish, She had charge of the joint Children's Care Committee Office at 136 St. George Street, where the arrangements for securing treatment for the ailments of the children attending the Highway, Blakesley Street, Lower Chapman Street, Cable Street Central, and the Lowood Street, Cable Street and Berner Street Special Schools [a mix of 'P.H.' - physical handicap - and 'M.D' - mental deficiency schools - see here for more details] were made. This work involves an enormous number of visits to the homes of children residing in the area (with the result, among others, that this is one of the best visited parishes in London), besides a huge correspondence with the London County Council (several departments), hospitals, treatment centres, and kindred agencies, such as the Invalid Children's Aid, Tuberculosis Care Committee, Skilled Employment Committee, War Pensions Committee, Juvenile Advisory Committee, and the like. No one without Miss Hatton's wide knowledge and experience could have undertaken the task. No one without her remarkable agility, energy, and speed of work, could have brought the work up to the high standard of efficiency to which, at no small sacrifice to her health, and with a complete sacrifice of leisure and other ties, she managed to bring it. The work in our office at 136 St. George's Street can safely challenge comparison with any work of the kind in England, and this we owe to Miss Hatton. Her work for the Rangers, and Guides and their Camp, was undertaken by her as a form of recreation! and was quite outside the circle of duties the Bishop sent her here to perform, but it was none the less appreciated by him. We desire to tender to her our grateful thanks, not unmixed with anxiety lest her strenuous years at St. George's may have made grave inroads upon her strength."

She later became Warden of the Katherine Low Settlement in Battersea (still active as a community centre), and then returned to the East End as Warden of St Hilda's Settlement, founded in 1889 by Cheltenham Ladies' College Guild, now St Hilda's East Community Centre.

Arabella Guendolin Savage-Armstrong (1924-25)

Miss Savage-Armstrong (1885-1931) worked here briefly at the same period, also living in the Rectory. She was the daughter of the Irish poet and scholar George Francis Savage-Armstrong, 'the poet of Wicklow and Down', professor of history and literature at Queen's College Cork, who died in 1906. Well-regarded in his day, he came under criticism from W B Yeats and is now considered a marginal figure in Irish literature. Family papers, including Guendolin's albums, photographs and commonplace books (including poetry by her father, Cowper, Thomas More, Coleridge and Wordsworth) are held at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA. She served as a nurse at the Richmond Military Hospital during the First World War. after which she was based at the Hackney Girls' Club before coming to this parish, and on her return to Ireland at the Sandes Soldiers' Home at Derry. Her notebooks reveal an intense religious devotion, and an interest in Christian Science and the ministry of healing.

In the magazine for February 1925 the Rector wrote: "During the 15 months that she has been amongst us she had worked unceasingly for the welfare of Pell Street Club, and few of its members can know how much time and thought she had given to it and to them. Her Sunday School class will miss her sadly, and the Wolf Cubs will perhaps mourn her departure most of all. For she has been the creator of the St. George's Pack, and very dear indeed has it been to her heart. We can only offer her our sincerest sympathy that an unfortunate accident had ended her work here, and our hopes for an early and complete recovery, and success in whatever work she undertakes in Ireland."

Margaret Emily Hallward (1921-26)

Miss Hallward came here because of family connections, and lived with her sister at 35 Prince's Square, a house owned by her aunt Caroline Hoare, who was clearly a formidable woman - she was a member of the banking family, which numbered several MPs, to whom the clergy often deferred (see here for an example); as the Rector J C Pringle wrote in the July 1924 magazine, when Miss Hoare was 82, "Remembering in the night, at home in Dartford, Kent, something she had wanted to say to her nieces the Misses Hallward, she got up at 5 a.m. on Monday morning, gathered her breakfast into a parcel, caught a "workmen's" and was knocking at the door of her old home, 35 Princes Square, at 8 a.m.! She called later at the Rectory, discussed some difficult points of theology and then, hearing that a friend of was ill, she demanded a Railway time table, and rushed off to catch at train to St. Albans!" She was one of the founders of the Lambeth Girls Evening Home; she died on 17 May 1929 at Dartford.

Pringle (by then ex-Rector) wrote this obituary of Miss Hallward in the May 1926 magazine:

Margaret E Hallward was born in Frittenden Rectory in 1868, one of a family of eleven. Her father who was Rector there found in her a valuable worker, but her conception of the service of Christ and her fellows involved, as she believed, more sacrifice of her personal inclination than this entailed. In 1900 her brother, John, was curate to the Rev. Arthur Dobson, Rector of Stepney, and Margaret joined the splendid band of workers the Rector had gathered around him to maintain the tradition of Church effort for which the Parish was already famous. She worked there for seven years; but them on the death of her father, she thought she ought to rejoin her family, and settled with them at Buxted, Sussex, and later at Frittenden. When her mother died in 1915 Margaret Hallward took up work for the Y.M.C.A. in the great Camp at Havre and remained there till 1919. In 1921 she felt again the appeal of the great task she had laid down for family reasons in 1907, and, believing she could do something to befriend some, perhaps many, of the East Londoners she had got to know and love in khaki at Havre, returned to Stepney. This time it was to a different Parish. The Rector of St. George-in-the-East was an old school friend of her brother John. She offered for work there and the offer was accepted with enthusiasm, and the work which she then undertook she was carrying on at full pressure up to within a few hours of her sudden death.

So much for the chronology of a life which in the remaining space available we will endeavour to appreciate. There was no small significance in Margaret Hallward's taking up residence at 35 Prince's Square. The house had been the home for many years of her aunt, Miss Caroline Hoare. It meant, therefore, the maintenance of a family tradition of social service. Both she and her aunt belonged in fact to one of those great and powerful clans of philanthropists which have been among the strongest and most splendid elements of English social life for two centuries. There were not a few points of resemblance in the characters of aunt and niece. Both were powerful and extremely courageous personalities. Both of them combined with all this force and determination a questioning spirit - a rare combination. Both of them cherished really deep attachments to those among their less fortunate neighbours with whom they became acquainted.

It was possible to observe in the working of Margaret Hallward's mind and in her activities the extent of the change which has come over both social philanthropy and philanthropic effort since she took up work in East London in 1900. In 1900 a parochial organisation like that of Stepney Parish Church was, apart from the Poor Law, practically the only agency on the spot for succour, uplift and amelioration. The Rector and his staff accepted the position as a permanent one and were out to build up means of rendering these services more and more effectually and for more and more people every year. They appealed confidently to all good people who believed in the future well-being of England to give them unstinted aid in money and effort. When Margaret returned to work in 1921 the Parochial situation had been completely revolutionised. An immense and complicated variety of public machinery had been set up to carry out the very objects for which she and her colleagues had worked at Stepney twenty years before. At the same time for a variety of reasons most thinking people had begun to question alike the wisdom and necessity of voluntary gifts and voluntary effort. Many were asking whether there out to be people with any surplus of money or time.

Margaret Hallward felt the full weight and significance of these changes, She was equally content to take her place performing small functions in a big piece of public machinery like the School Care Committee Organisation, and to spend an afternoon listening to the schemes of her "Labour" acquaintances for turning the social fabric upside down. But all the while she was demonstrating triumphantly that all the philosophic questioning and all the administrative developments had failed between them to produce anything of equal value with personal work and home visiting based upon love of God and man. The wonderful thing about her was that with all her own strength and deep moral sense she could cling with an unconquerable optimism to the belief that the apparently feeble and incompetent would prove themselves one fine day, if only given a chance, strong and efficient., It is hardly necessary to add that she was a worker of quite unique value in a Parish like St. George-in-the-East.

Her questioning attitude in social economics did not shake her strong Churchmanship or her unflagging zeal as a Sunday School and Bible Class teacher, She brought into the grimy surroundings of St. George's her great love of beautiful things, whether in the gardens of Kent, the snows of Switzerland, or the Lakes and Cities of Italy. She loved these things in proportion as they could be made available for her friends, and at the time of her death had just refused to accompany her sisters on a long Italian holiday rather than leave those whom she knew so well to befriend under the shadow of London Dock wall.

One of the many delightful aspects of her service was her genius for bringing other members of her family and clan into it. Her fellow workers will not readily forget the frequent appearances of the Hallward and Hoare connection laden with country produce for decorations or sustenance.

All those who loved her, and in forlorn and hesitating moments loved to lean upon her great strength and firmness of purpose, are thankful that she passed so swiftly and painlessly to the next stage of her service for the Master; but if we dare repine we would fain ask "Lord why so soon?" J.C.P.

The Bishop of Stepney, Henry Mosley, wrote on 27 March 1926

"My dear Rector, I wish I could have been with you and your people tomorrow evening, but it is impossible. St. George's parish has had in Miss Hallward one for whose presence, influence and work they will always thank God. Those who like myself have known her at all intimately will say: "Every thought of her is blessed, every memory good." Her love, her influence, must continue. Death cannot destroy them. There is the momentary shock and bereavement, but in Christ there is greater love, life and service. Tell her many friends how real is my sympathy with them. Yours very sincerely, HENRY STEPNEY."

Miss G. Turner (1925-28)

Miss Turner came in May 1925 with the new Rector C J Beresford, and lived above the Mission House at 136 St George's Street [later 181 The Highway]; she finished regular work in the parish in August 1928, but returning once a week to help with Care Committee and to continue her collecting for the Bank.

Miss Gladys F. Stone (1928-30)

In the magazine for September 1928 the Rector wrote "Miss G F Stone hopes to begin her work in the Parish on September 15th. She was trained at St. Christopher's College, Blackheath, and brings to her work a wide experience both at home and abroad.... She too lived at 136 St George's Street." In the magazine for July 1930 he wrote "Everyone will regret that Miss Stone feels it necessary to seek less arduous work, and will be leaving us about the middle of July. We owe her much for her faithful and kindly work throughout the parish, and it will be very difficult to fill her place, especially in the Kindergarten and with the Brownies, We shall all hope that she will find happy work and better health in the West London parish to which she is going." This was St Thomas' Shepherd's Bush.

Miss E. Burn (1930-34)

Miss Burn replaced Miss Stone at the Mission House, and took over her work. In Sptember 1934 the Rector wrote "Miss Burn will be leaving us at the end of September. She will be sadly missed by the many friends she has made in the Parish during her four years amongst us, and will carry with her the good wishes of all for whatever work she may go to. She has hopes of being able to give her services in some bits of the work here, but this will of course depend upon the demands made upon her by whatever her new work may be. Her going means the going of Miss Cattell too, but she also has kindly offered to continue some of her much valued work with the Brownies. So our farewells to these two ladies will be cheered by the hope that we may not lose them altogether."

Sister A. Reason (1934-??)

A Church Army sister replaced Miss Burn from October 1934, coming from south Wales, though she had previously worked in Hoxton.

Nora Kathleen Neal MBE (1943-??)

Nora had trained for parish work at St Andrew's House, and served as a licensed worker in Hackney before coming to St George-in-the-East. She arrived in 1943, to join the wartime team under Fr Groser that was maintaining ministry to a blitzed and struggling community. Her home was at St John's House, 13 Christian Street. Among other things, she ran a club for girls.

In 1957 (officially licensed the following year) Nora became the first worker at Church House, Wellclose Square with Fr Joe Williamson, having first spent a period doing additional training in 'moral welfare work'. Initially she lodged with Mrs Maaser at 4 Wellclose Square - more than once giving up her bed to a young girl off the streets - but in due course moved into Church House itself. (Curiously, she is listed in diocesan archives of the period as 'Miss D.J.H. Neal'.) In the following year, as the work expanded, she was joined by Daphne Jones (see below).

Nora began retirement as warden at Megg's and Goodwin's Almhouses (founded by Meggs in Whitechapel Road in 1658, 'repaired, improved and further endowed' by Benjamin Goodwin and rebuilt in 1893 in Upton Lane, Forest Gate). She returned to Stepney, first to a bedsit in Tredegar Square and then to a flat at Toynbee Hall, where, as Olive Wagstaff says, she was a great help and encouragement to all her friends and neighbours. At the ago of 80 she moved to Compton Durville in Somerset, the mother house of the Community of St Francis - she was a Franciscan tertiary for 46 years. She played an active role in the House, helping novices and visitors, and when she died there, aged 91, was buried in the grounds.

Daphne Jones

Daphne Jones was a parish worker at All Saints Poplar for an astonishing 55 years - for a few of which she was 'on loan' to St Paul's and the work at Church House Wellclose Square. In her time she served with six rectors and about sixty curates. She was born in 1915 into a rather grand family at Morgan Hall in Fairford, Gloucestershire (where she ended her days: see this interview); her father lived the life of a country gentleman, and social life was dictated by the niceties of calling cards. This meant that in later life she was at ease mixing with the 'great and the good' when their help was needed. Her Anglo-Catholic boarding school in Bexhill-on-Sea supported a mission in the Euston area, and she was inspired at confirmation by Fr Basil Jellicoe, founder of the St Pancras Housing Association, to 'do something'. During the war, she trained as a nurse at St Thomas' Hospital, and ran a 100-bed unit for battlefield victims at Chertsey. in 1946, Mark Hodson, Rector of Poplar (later Bishop of Hereford) invited her to join his staff; meanwhile, she had trained as a midwife and Queen's Nurse, and was soon part of a team providing services across the whole borough, with 6,000-7,000 visits a year. She remained in touch with many of the families for the rest of her life.

A new ministry opened up to her when at a bus stop she met 'Mary', a young Irish girl, heavily pregnant and with no hospital bed booked. Daphne went 'home' with her - a room over a cafe shared with five Indians. This was her introduction to the brothels of Dockland, and the cause of her accepting Fr Joe's invitation to join his 'rescue' ministry. Like him, she remained in contact with many of the girls and their babies (including the original Irish girl's baby).

She - like Nora Neal above - was a member of the Franciscan Third Order, and lived in great simplicity. She was undoubtedly one of the heroines of the East End, and features in the Poplar Saints Memorial Icon.

The story of 'Mary' features in a fictional but semi-autobiographical account of East End midwifery in the 1950s - Jennifer Worth Call the Midwife (Merton Books 2002, Phoenix 2008). The chapters on Cable Street are dedicated to Fr Joe and Daphne Jones. The religious community where she lived and trained, which in the book she she calls 'St Raymund Nonnatus', was in fact the Nursing Sisters of St John the Divine, founded from King's College Hospital in 1848 and one of the few sources of skilled midwifery in the period when the profession was not taken seriously (this changed with the 1902 Midwives Act). They were active in Poplar from at least the 1880s, and provided a borough-wide service in the days before Stepney Council took over responsibility in the years after the Second World War. Daphne Jones did some of her training with them; one or more of them was on the staff of the parish church. They were popularly known as the 'Bluebags' because of their habit.

Jennifer Worth, who died in 2011, also wrote Shadows of the Workhouse (2005), an account of the period when the workhouses were closed but their ethos and practices lingered on, and Farewell to the East End (2009), with further tales of midwifery.

Dorothy Halsall MBE

Dorothy Halsall served here for a year with Fr Groser, before moving with him to the restored Royal Foundation of St Katharine, becoming one of the original members of the community there; she died in 2010 at the age of 98. Here is a tribute from Mary Whybray who (like Olive Wagstaff) was a close friend until Dorothy's death in 2010. Mary was living in Canada at the time, and produced this for her daughter (and Dorothy's god-daughter) Elizabeth to include at Dorothy's funeral:

"On my bookshelves I have a book of which I am very fond. It is a book of photographs of East London and it has one of 13 Christian Street, Stepney. That was the place that I first met Dorothy Halsall. It was not a chance meeting for me. I was at the time at William Temple College, where I had met a close friend of Dorothy's who had worked with her in Sheffield. She knew that Dorothy was working in the parish of St George-in-the-East but was about to move to the Royal Foundation of Saint Katharine to work with Father John Groser, and so it came about that I replaced Dorothy at St George's, and thus a strong and lasting friendship was established. I learned so much from her seeing how she related to others of all descriptions - the young, the elderly, the tough seafaring men coming to be in the house run by the Franciscan brothers on Cable Street just around the corner from Christian Street. But for the eight years that I was there it was her work with the elderly people that made the strongest impression on me. She was regularly at a lunch club held in the hall at St George's, where the people loved her and where she was happy to give them advice when they asked for it, but never patronised them. All over the area there were and still may be people who are deeply indebted to Dorothy for the help and care she gave them, and within the Foundation itself she could always be found by women workers like myself who were thankful to consult her about their work and its problems, which were never in short supply. It was a real joy to many when she was in the Queen's New Year's Honours List - so well deserved. Her Christian faith was always deeply important to her and many years later when I visited her in Havant it was very moving to discover the reality of her prayer life and the inclusion of so many friends – those from the past as well as many new friends, and many world-wide causes and prayers for world peace."

Mary Dudman (later Carmack/Whybray) (1947-56)

Mary left school at 18, during the Second World War, and trained as a teacher at Southlands College (a Methodist foundation, originally in Battersea, relocating to Wandsworth but evacuated during the war to Weston-super-Mare – it is now part of the University of Roehampton). She taught in Dagenham for a time, leaving for another post in Basingstoke, to enable her to care for her mother who had cancer. When her sister was demobbed and able to share this care, Mary offered herself for lay ministry and attended a selection conference in Newcastle; she trained at William Temple College (newly-established in 1947 at Hawarden (Gladstone's library) before its move to Rugby in 1954, and to Manchester in 1971, becoming the William Temple Foundation). Turning down the offer of a job teaching religious studies at a teacher training college in Bedford, she returned to William Temple College, where she met Pamela, there for a term's respite from working as an actor in the steel foundries of Sheffield, who knew Dorothy Halsall and suggested St George-in-the-East as a possible sphere of work; a few weeks later Dorothy was appointed to become part of the lay community at the Royal Foundation of St Katharine's, so there was a vacancy here. Mary came to London, taking the pastoral care course for ordinands at King's College London (taught by the Dean, Eric Abbott and moved into 13 Christian Street – initially with Norah Neal. She commented:

"We used the big room on the ground floor for meetings and discussions and for a place where children could come after school … The house was just round the corner from Cable Street and near the Franciscan house where the brothers ran a club for men who worked on the ships that would come into the docks, and Father Neville used to come to the staff meetings on Monday mornings at the Rectory. Opposite the house … was Christian Street School (run by the London County Council), and next to the house a small synagogue where the Jewish children went for instruction and not far away was Fairclough St School [now Harry Gosling School], also run by the LCC … which kept the Jewish festivals and started early on Fridays and finished early so that the Jewish Sabbath could be observed. From the start of my time in Stepney I went twice a week in the mornings to teach the Christian children scripture. The Church itself when I came was a pre-fab within the stone walls of the original church which had been seriously damaged by the bombing. There was a said Eucharist each morning, and on Sundays a Sung Eucharist at 9.30am with a Eucharist at 11.30am for the children, with a kind of commentary for the children to help them to understand what it was all about. I did a lot of visiting of the families of the children who came to church. During that time I arranged to take a group of children to an old house in a village in Hampshire which had a garden on the river Test where my mother was born and some member of her family had lived for the last 300 years … It was a great time for all of us and especially for me since I had spent a lot of time there as a child."

Mary moved from 13 Christian Street into the Rectory to look after the Boggis children after an accident in which Lotte was injured; meanwhile, someone else moved in there, so when Lotte returned home Mary ended her time here in a flat on Cable Street. This was a busy time in the parish: there was a lunch club for pensioners in the church hall, with a games afternoon, and a chiropodist in attendance. Dorothy Halsall was by now running work with the elderly from St Katharine's, where they met workers from other parishes, including Olive Wagstaff, then on the staff at St Dunstan Stepney. In 1953 Eric Abbott provided two curates from King's London: John Eldrid (1953-56), who went on to become a senior figure in The Samaritans, and David Grant (1953-54). As the population of the parish was changing, with many Africans and Caribbeans moving into the area, Mary with Joan Miller visited Nigeria, as she said, because we wanted to understand people as well as we could.

When Jack Boggis left the parish in 1955 for Hillingdon – succeeded by an incumbent of a somewhat different stamp – Mary went to work full time at Fairclough Street School, until she met her first husband, Murray Carmack (later known as Ross Alden), a Canadian musician here on a teaching exchange; they married in 1957 and lived in Canada for the next 20 years, where their daughters Catherine (who died in 2003) and Elizabeth were born. He died in 2008; the Vancouver Sun memorialised him as pianist and teacher, born in the Canadian wilderness; fellow of Trinity, London; baccalaureate at Durham; magister at Harvard [who in 1967 published his edition of The So-Called John Sturt Lute Book]; matriculant at Oxford; sojourner in five countries; beloved of thousands of children. To challenge he brought resource, to adversity he brought fortitude, to struggle he brought endurance.

In 1979, on a return visit to England, Mary met and married an old friend, recently widowed, Norman Whybray, professor of Hebrew and Old Testament at Hull University and author of several books; he retired in 1988 and died ten years later.

Ethel Upton

Ethel Upton also came to work with Fr Groser. In 1947, with Dorothy Halsall and Olive Wagstaff she was a key founder of the highly-effective Stepney Old People's Welfare Association - now known as THFN, Tower Hamlets Friends and Neighbours. See further Kenneth Leech Through our long exile: contextual theology and the urban experience (DLT 2001). Ethel lived for a time after the War at 400 Commercial Road, the former vicarage of St John's.

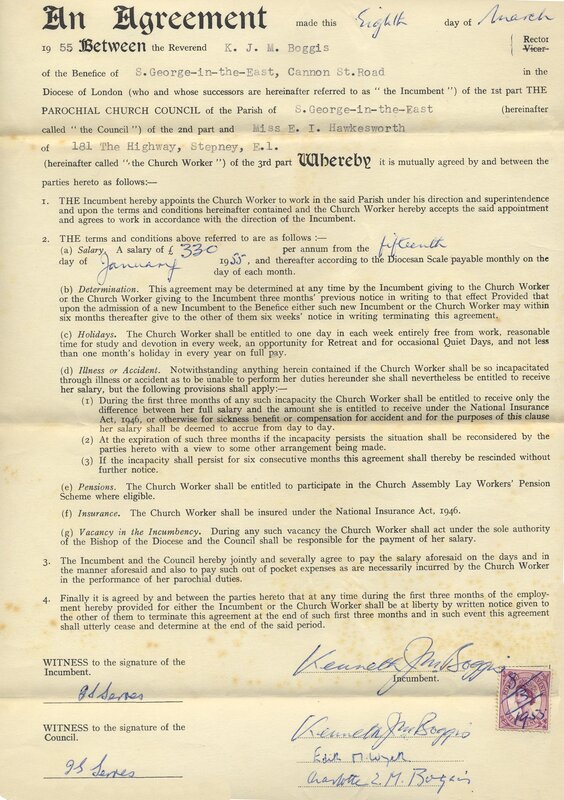

Miss Edie Ilene Hawkesworth

Edie was a friend of Mary Dudman from William Temple College, and had qualified as a teacher at Leeds University in 1953. She came initially to the Royal Foundation of St Katharine's, but the work was not what she expected so she transferred here in 1955. She lived in rooms on the first floor of the Mission House, 181 The Highway, and was paid a salary of £330 a year (later reduced to £315). Below is a copy of the agreement under which she, like other lay workers of the time, were employed: a probationary period of three months; three month's notice by the incumbent (except that on a change of incumbent either party could give six weeks' notice); answerable directly to the bishop during a vacancy; and arrangements for holidays, sickness, insurance and pension. Edith Wyeth's daughter Jenefer (who had a holiday with 'Hawky' and her niece on the Isle of Wight, where her family came from) remembers her as a jolly lady, maybe a little eccentric, who would do anything for anybody. One of her duties was cleaning the prefab, and she showed Jenny how to remove candle wax from carpets with brown paper and a hot iron, and also how to sweep the dirt through a loose floorboard into the void below. Like many of her ilk, she kept a bottle of smelling salts in her bag. After another parish post, she went to work at Boston High School for Girls in Lincolnshire; there she was the local rep for the Assistant Masters & Mistresses Association. She retired to Whittington College, sheltered housing provided by the Mercers' Company, on the London Road in Felbridge, East Grinstead, where Edith visited her on several occasions.

Trudi(e) Eulenberg

Trudi(e) was the daughter of Dr Kurt Eulenberg who rescued the famous family music publishing firm in Leipzig (with their distinctive small, yellow-backed scores), which he had taken over from his father Ernst in 1926, when it was expropriated by the Nazis in 1939 and the family fled to Zurich. In 1940 an Italian court held, surprisingly, that the German Commissar, rather than the company, was entitled to outstanding foreign debts; but Kurt set up a London base via Goodwin & Tabb, and moved here in 1945 to rebuild their portfolio – with great success; it was taken over by Schott in the 1950s, and he retired in 1968 aged 90.

Trudi was Ranyard-trained, and worked here for a time - a Wyeth family saying, Oh Jimmy, you are so wonderful (when he had helped her in the garden) reflects her distinctive idioms. But as the following extracts from Malcolm Johnson Diary of a Gay Priest show, by 1974 she was working at St Botolph Aldgate:

Morwenna Tredinnick

Morwenna trained with the 'Grey Ladies' and served in Southwark diocese before coming here as parish worker in Fr Solomon's time. She remained after the Solomons' departure, living initially in the first floor flat of the Mission House, then in one of the church flats, until retirement in 1979, when she moved to a flat in Tarling House and then to Montpelier Place, where she died in 2006 at the age of 95. Under her bed was discovered a silver tankard presented to the Newcastle architect John Green when his Scotswood Chain Suspension Bridge spanning the Tyne was opened in 1831 (it was demolished in 1967) - she was his great-great-granddaughter.

Olive Wagstaff

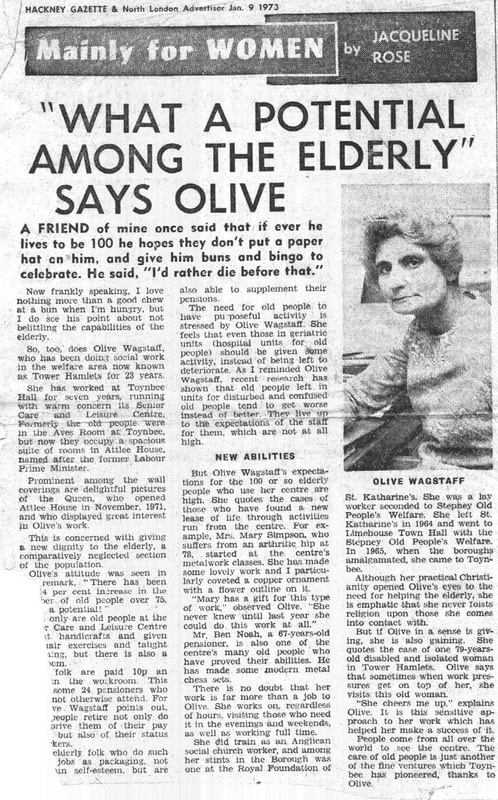

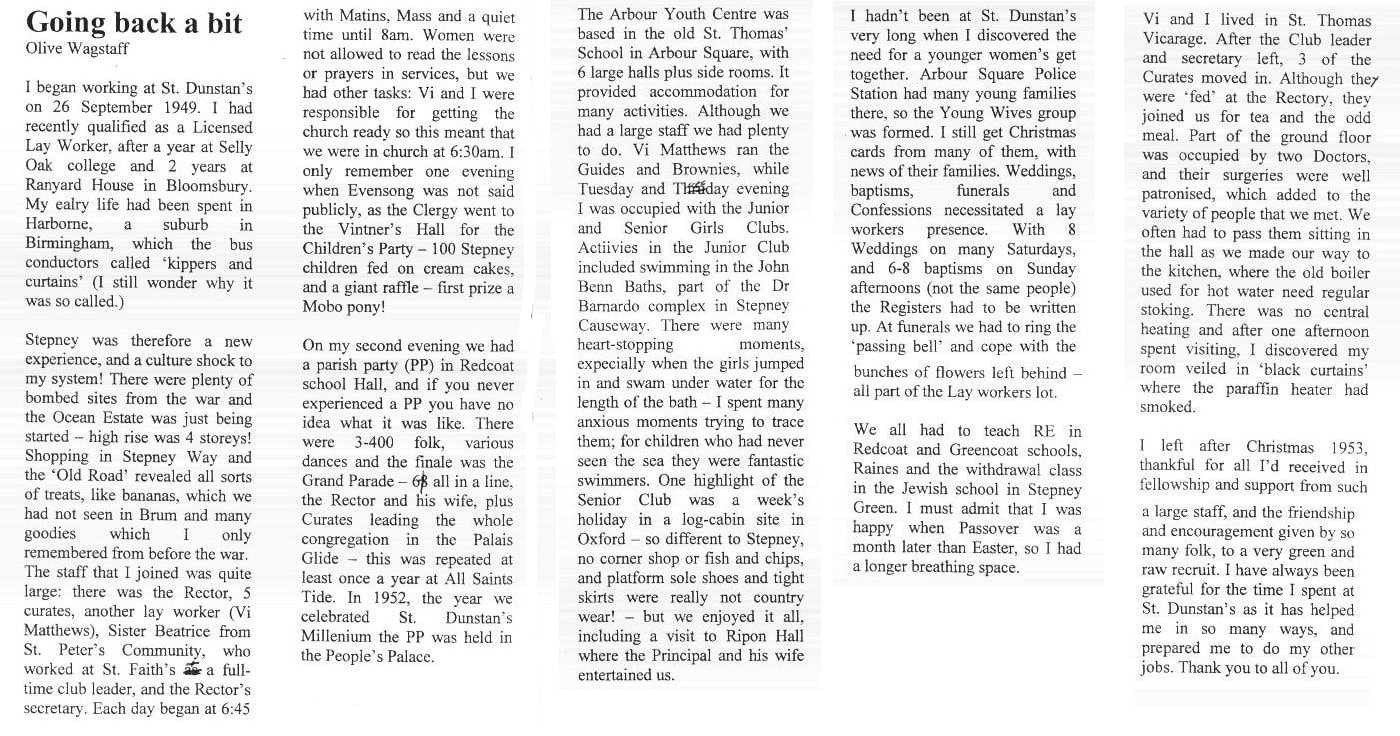

Olive was licensed as an accredited worker in 1949 (we celebrated her 60th anniversary in 2009), and has been part of our parish life for many years both before and after her retirement, serving for various periods both as churchwarden and sacristan, and leading worship at St Paul Dock Street prior to its closure. She began her training at Selly Oak (for she is a Brummie), and after a further two years training with the Ranyard Mission worked at St Dunstan Stepney from 1949-53 - see her article in their magazine [below] for a restrospect of those days, interesting both for the heavy expectations laid on women workers and for what, ridiculously, they were barred from doing. She then became one of the original members of the resident lay community at the Royal Foundation of St Katharine under Fr Groser. From here she was seconded to help run Stepney Old People's Welfare, leaving St Katharine's in 1964 to work from Limehouse Town Hall, and the following year (after local government reorganisation) from Toynbee Hall, where she lived for some years, running the Senior Care and Leisure Centre, which was based in Attlee House opened by the Queen in 1971. Also below is an account of this work from the Hackney Gazette of 9 January 1973.

Olive's home for many years has been the 22nd floor of Shearsmith House on the St George's Estate, from which she has seen it all happen (including the 'Siege of Wapping' in 1986). In 2010 she was one of five long-term Tower Hamlets residents, from different faith communities, featured in a film East End Lives [URL seems no longer to be live] by Hazuan Hashim and Phil Maxwell. In her final years, having campaigned vigorously for the elderly of the area for much of her life, was herself a recipient of its social services, and comments on the experience in an article [below] from East End Life (6 June 2011); she died in June 2015.

A note on training

In the 19th century, London pioneered the training of women for lay parochial ministry, with several diocesan or local institutions. Most of them were initially associated with the development of deaconess ministry, which was much-influenced by the community-based model of the Kaiserwerth movement in Germany (where Florence Nightingale trained; some of its members nursed at the German hospital in East London opened in 1845. Some institutions specialised in nursing (see the note above on the Nursing Sisters of St John the Divine, which ran training programmes for 'lay' midwives), some in visiting and general parochial work, some in teaching. Across London there were a number of 'settlements' where women workers lived.

One of the earliest, and most innovative schemes – for it provided the first paid social workers, and then district nurses – began in 1857 as the London Bible and Domestic Female Mission. Ellen Ranyard (1809-79) was the daughter of a London cement maker, and as a child encountered the homes of the poor. Her organisation first trained working-class women in 'poor law, hygiene and scripture' to become 'bible women' in their home areas - a cross between missionaries and social workers – under the supervision of middle-class superintendents. By 1867 there were 234 workers across London. To this were added, the following year, 'bible nurses': also working-class women, with hospital training. By 1894 a team of 80+ made over 200,000 visits a year. Nursing training ended in 1907 as hospitals took on the role, but Ranyard Nurses continued to make a contribution up to and beyond the introduction of the NHS. Renamed the Ranyard Mission in 1917, and based in the Holborn area, it continued to train women for parish work. The Friends of Ranyard now run homes in Blackheath - Mulberry House, Dow House and Kingswood Halls. Olive Wagstaff trained here, and found it a rich experience; so too did Trudi Eulenberg. Although numbers after the war were small, they drew on all the resources of London – lectures at King's College and SOAS, and site visits to places such as courts, hospitals and even waterworks.

Here is a report from 1871:

Mrs. Ranyard, in her Missing Link Magazine, states that the supporters of ihe Bible Women's Mission have enabled her to maintain, during the past year, 222 Bible women. The total receipts last year were £17,179; the total expenditure, £17,414. The donations to special districts and to the general or working fund were £11,808 17s l0d. The lady superintendents received in payment from the poor last year: For Bibles, £785 5s 8d; for clothing, beds, soup, £4,584 17s 6d; total payments from the poor, £5,370 3s 2d. The expenditure of the mission includes: For salaries to Bible-women, £6,865 18s 9d; payments for Bibles, £698 16s 7d; returned to the poor in clothing material and by payments for work, £4,926 15s; and rent and furniture, with light and fire in Mission-rooms, £2,221 6s Id. The mission has supplied nine Bible-women to country districts. Thirteen women have been trained with the Bible-women previous to their hospital training as nurses. The mission has paid salary from its foreign fund in aid of native Christians employed as Bible-women abroad, or for purely Bible work. It has six Bible-women in Beyrout and Damascus, twelve at Ooroomiah (in Persia), three or four in India and Burmah, two in Madagascar, one in Jerusalem, two in Lodiana, one in Marseilles, one for the French at New York, one in Jamaica, one in Demerara. Within the last fourteen years there has passed through the hands of the Lady Superintendent of the mission for various Bible mission purposes a sum not far short of two hundred thousand pounds: £116,874 in voluntary donations to the first work; £10,646 payments of the poor for Bibles; £58,790 for clothing from the poor; total £186,310. £5,257 for mother-house and Bible-women nurses, inclusive of £1,309 spent in food, clothing, &c., to patients; £5,091 for Dudley-street and Parker-street dormitories; £1,054 for Mr. Moon's Bibles for the blind; and £2,065 for foreign fund to place Bible-women on foreign stations when providentiul openings occur: total £199,777.

In 1860 the Missionary Training College began in East London, which later became Mildmay House - but although the founder William Pennefather was a Church of England minister, he never sought episcopal approval, and it was never specifically Anglican. 'Mildmay deaconesses' trained for two years, and worked in parishes at the invitation of the incumbent; they also maintained two hospitals, and nursing later became the primary focus of their work.

In 1880 an East London Deaconess Institution was established, with Bishop Walsham How's encouragement, to provide deaconesses and church workers, and also 'associates' - self-financing ladies of means who lived by the rule and wore the robes of the community, but who 'came and went'. This house continued until 1924.

Isabella Gilmore (1842-1923) was William Morris' sister. She trained as a nurse, and was encouraged by Bishop Thorold of Rochester to pioneer deaconess work in South London [Southwark diocese was not created until 1905]. At first she was reluctant, but was made deaconess in 1887, and set up a training house in Park Hill, moving to premises on Clapham Common North Side in 1891 - her brother designed the chapel and she, being practical, fixed the drains. This handsome 18th century house had been built, as 'The Sisters', for John Walter, founder of The Times; it was later renamed Gilmore House in her memory. Many women trained here for parish ministry. When it closed in 1970, it became flats for overseas students and families, and is now a 'luxury' development. The Isabella Gilmore Fund continues to support women called to ministry in Southwark diocese.

The focus of the 'Grey Ladies' - officially the College of Women Workers, established in 1892 by the Bishop of Southwark's sister at Blackheath Hill - was parochial teaching work. After a period of probation and training, they were admitted to the college by the bishop, and worked under his authority and that of their incumbents. They had branch houses elsewhere.

In 1909 St Christopher's College, Blackheath was founded by the Revd William Hume Campbell to train RE teachers for day and Sunday schools. The one (later two) year certificate course combined theology (biblical study, doctrine, church history and 'prayer book') with the theory and practice of education (including psychology, teaching methods, Sunday School organisation and the history of education). It tended to attract middle-class women, some from independent schools. Some worked as diocesan Sunday School organisers, supporting volunteers; others became missionaries in various parts of the Empire (including the western Canadian frontier). One distinguished alumna was the late Margaret Kane, the first female industrial chaplain (in Sheffield) and later adviser on social and industrial affairs to successive Bishops of Durham; she was ordained deacon at the age of 73, and priest at 80. On closure, in 1971 the college became an educational trust, part of the Association of Church College Trusts linked to the National Society promoting RE in accordance with the principles of the Church of England, in parishes and schools, with an annual income of about £100k.

In 1919, with a growing concern for professionalism, certificates were issued to women who had trained in theology, teaching and social studies - but they were very poorly paid. 1930 saw the start of the three-year Inter-Diocesan Certificate (IDC), which became the normal qualification for parish work, and training was to a high standard. In 1966 there were said to be 307 parish, or accredited lay, workers (ALWs). Their traditional liturgical dress is a burgundy robe or scarf, with a medallion, and a silver lapel badge for street wear. Very few remain in paid work, since the ordination of women (the office of ALW was opened to men in 1972) - about one a year goes into training, for specialised ministries - but those who are retired, including our own Olive, have an honoured place in the story of the 20th century church.

Over the years many women have served the churches of the parish as full-time workers with skill and devotion. As the following notes show, some came from 'grand' families, drawn to service in the East End like those who joined the emergent religious communities for women. Over time, their commitment to the area was informed by rigorous training (more so than that of their male counterparts): some would doubtless have been accepted for ordained ministry if this had been possible in their time. Here are accounts of some of them.

Emily FitzHardinge Berkeley

Miss Berkeley was born in Agra, India in 1862. She was a member of a titled family, a relative of the Hon Fitzhardinge Berkely MP, whose son appears in lists of prominent converts to Roman Catholicism. She lived in the Rectory, working in the parish until about 1920. In November 1924 the Rector wrote "Miss Emily FitzHardinge Berkeley will be remembered by many readers of this magazine, although failing health brought her active work in the parish to an end four years ago. She was a considerable sufferer but managed to keep in touch with many of her old friends till the end. When able to go out, she has attended St. Paul's, Shadwell, finding the steps up to St. George's a serious matter owing to her weak heart. She was a most Devoted worker, always willing to spend herself and all she has for Christ, but never, if she could help it, a penny upon herself. Her example will long live with us."

Phyllis Hatton (1919-25)

Phyllis Hatton worked in the parish in the early 1920s, living in the Rectory. When the Revd J C Pringle came as Rector after the War, congregational numbers were low and the Bishop would not authorise a curate, preferring to appoint 'women workers' to organise the pastoral work. Miss Hatton was primarily involved with committee work, in a style which the Rector, himself committed to this approach, no doubt approved despite his regret at being denied a clerical colleague. Her work with the clubs and societies of the parish was an 'extra', and suggests she was a workaholic (she had some periods of stress-related absence). His farewell tribute in the April 1925 magazine - he left at the same time, the reason for her being moved to diocesan work - hints at this:

"Miss P.M. Hatton has left us after 5½ years of most strenuous service in the parish. The Diocesan Board of Women's Work announced that for two years they have regarded her as just the person for their work, and that they had thought this a good opportunity of securing her services. She entered upon her duties at the London Diocesan House, 33 Bedford Square, at the beginning of March. She has our best wishes for her health and strength and success in her new work. Miss Hatton was specially approved by the Bishop of Stepney for the task of organising the Social Service of this parish, She had charge of the joint Children's Care Committee Office at 136 St. George Street, where the arrangements for securing treatment for the ailments of the children attending the Highway, Blakesley Street, Lower Chapman Street, Cable Street Central, and the Lowood Street, Cable Street and Berner Street Special Schools [a mix of 'P.H.' - physical handicap - and 'M.D' - mental deficiency schools - see here for more details] were made. This work involves an enormous number of visits to the homes of children residing in the area (with the result, among others, that this is one of the best visited parishes in London), besides a huge correspondence with the London County Council (several departments), hospitals, treatment centres, and kindred agencies, such as the Invalid Children's Aid, Tuberculosis Care Committee, Skilled Employment Committee, War Pensions Committee, Juvenile Advisory Committee, and the like. No one without Miss Hatton's wide knowledge and experience could have undertaken the task. No one without her remarkable agility, energy, and speed of work, could have brought the work up to the high standard of efficiency to which, at no small sacrifice to her health, and with a complete sacrifice of leisure and other ties, she managed to bring it. The work in our office at 136 St. George's Street can safely challenge comparison with any work of the kind in England, and this we owe to Miss Hatton. Her work for the Rangers, and Guides and their Camp, was undertaken by her as a form of recreation! and was quite outside the circle of duties the Bishop sent her here to perform, but it was none the less appreciated by him. We desire to tender to her our grateful thanks, not unmixed with anxiety lest her strenuous years at St. George's may have made grave inroads upon her strength."

She later became Warden of the Katherine Low Settlement in Battersea (still active as a community centre), and then returned to the East End as Warden of St Hilda's Settlement, founded in 1889 by Cheltenham Ladies' College Guild, now St Hilda's East Community Centre.

Arabella Guendolin Savage-Armstrong (1924-25)

Miss Savage-Armstrong (1885-1931) worked here briefly at the same period, also living in the Rectory. She was the daughter of the Irish poet and scholar George Francis Savage-Armstrong, 'the poet of Wicklow and Down', professor of history and literature at Queen's College Cork, who died in 1906. Well-regarded in his day, he came under criticism from W B Yeats and is now considered a marginal figure in Irish literature. Family papers, including Guendolin's albums, photographs and commonplace books (including poetry by her father, Cowper, Thomas More, Coleridge and Wordsworth) are held at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, UCLA. She served as a nurse at the Richmond Military Hospital during the First World War. after which she was based at the Hackney Girls' Club before coming to this parish, and on her return to Ireland at the Sandes Soldiers' Home at Derry. Her notebooks reveal an intense religious devotion, and an interest in Christian Science and the ministry of healing.

In the magazine for February 1925 the Rector wrote: "During the 15 months that she has been amongst us she had worked unceasingly for the welfare of Pell Street Club, and few of its members can know how much time and thought she had given to it and to them. Her Sunday School class will miss her sadly, and the Wolf Cubs will perhaps mourn her departure most of all. For she has been the creator of the St. George's Pack, and very dear indeed has it been to her heart. We can only offer her our sincerest sympathy that an unfortunate accident had ended her work here, and our hopes for an early and complete recovery, and success in whatever work she undertakes in Ireland."

Margaret Emily Hallward (1921-26)

Miss Hallward came here because of family connections, and lived with her sister at 35 Prince's Square, a house owned by her aunt Caroline Hoare, who was clearly a formidable woman - she was a member of the banking family, which numbered several MPs, to whom the clergy often deferred (see here for an example); as the Rector J C Pringle wrote in the July 1924 magazine, when Miss Hoare was 82, "Remembering in the night, at home in Dartford, Kent, something she had wanted to say to her nieces the Misses Hallward, she got up at 5 a.m. on Monday morning, gathered her breakfast into a parcel, caught a "workmen's" and was knocking at the door of her old home, 35 Princes Square, at 8 a.m.! She called later at the Rectory, discussed some difficult points of theology and then, hearing that a friend of was ill, she demanded a Railway time table, and rushed off to catch at train to St. Albans!" She was one of the founders of the Lambeth Girls Evening Home; she died on 17 May 1929 at Dartford.

Pringle (by then ex-Rector) wrote this obituary of Miss Hallward in the May 1926 magazine:

Margaret E Hallward was born in Frittenden Rectory in 1868, one of a family of eleven. Her father who was Rector there found in her a valuable worker, but her conception of the service of Christ and her fellows involved, as she believed, more sacrifice of her personal inclination than this entailed. In 1900 her brother, John, was curate to the Rev. Arthur Dobson, Rector of Stepney, and Margaret joined the splendid band of workers the Rector had gathered around him to maintain the tradition of Church effort for which the Parish was already famous. She worked there for seven years; but them on the death of her father, she thought she ought to rejoin her family, and settled with them at Buxted, Sussex, and later at Frittenden. When her mother died in 1915 Margaret Hallward took up work for the Y.M.C.A. in the great Camp at Havre and remained there till 1919. In 1921 she felt again the appeal of the great task she had laid down for family reasons in 1907, and, believing she could do something to befriend some, perhaps many, of the East Londoners she had got to know and love in khaki at Havre, returned to Stepney. This time it was to a different Parish. The Rector of St. George-in-the-East was an old school friend of her brother John. She offered for work there and the offer was accepted with enthusiasm, and the work which she then undertook she was carrying on at full pressure up to within a few hours of her sudden death.

So much for the chronology of a life which in the remaining space available we will endeavour to appreciate. There was no small significance in Margaret Hallward's taking up residence at 35 Prince's Square. The house had been the home for many years of her aunt, Miss Caroline Hoare. It meant, therefore, the maintenance of a family tradition of social service. Both she and her aunt belonged in fact to one of those great and powerful clans of philanthropists which have been among the strongest and most splendid elements of English social life for two centuries. There were not a few points of resemblance in the characters of aunt and niece. Both were powerful and extremely courageous personalities. Both of them combined with all this force and determination a questioning spirit - a rare combination. Both of them cherished really deep attachments to those among their less fortunate neighbours with whom they became acquainted.

It was possible to observe in the working of Margaret Hallward's mind and in her activities the extent of the change which has come over both social philanthropy and philanthropic effort since she took up work in East London in 1900. In 1900 a parochial organisation like that of Stepney Parish Church was, apart from the Poor Law, practically the only agency on the spot for succour, uplift and amelioration. The Rector and his staff accepted the position as a permanent one and were out to build up means of rendering these services more and more effectually and for more and more people every year. They appealed confidently to all good people who believed in the future well-being of England to give them unstinted aid in money and effort. When Margaret returned to work in 1921 the Parochial situation had been completely revolutionised. An immense and complicated variety of public machinery had been set up to carry out the very objects for which she and her colleagues had worked at Stepney twenty years before. At the same time for a variety of reasons most thinking people had begun to question alike the wisdom and necessity of voluntary gifts and voluntary effort. Many were asking whether there out to be people with any surplus of money or time.

Margaret Hallward felt the full weight and significance of these changes, She was equally content to take her place performing small functions in a big piece of public machinery like the School Care Committee Organisation, and to spend an afternoon listening to the schemes of her "Labour" acquaintances for turning the social fabric upside down. But all the while she was demonstrating triumphantly that all the philosophic questioning and all the administrative developments had failed between them to produce anything of equal value with personal work and home visiting based upon love of God and man. The wonderful thing about her was that with all her own strength and deep moral sense she could cling with an unconquerable optimism to the belief that the apparently feeble and incompetent would prove themselves one fine day, if only given a chance, strong and efficient., It is hardly necessary to add that she was a worker of quite unique value in a Parish like St. George-in-the-East.

Her questioning attitude in social economics did not shake her strong Churchmanship or her unflagging zeal as a Sunday School and Bible Class teacher, She brought into the grimy surroundings of St. George's her great love of beautiful things, whether in the gardens of Kent, the snows of Switzerland, or the Lakes and Cities of Italy. She loved these things in proportion as they could be made available for her friends, and at the time of her death had just refused to accompany her sisters on a long Italian holiday rather than leave those whom she knew so well to befriend under the shadow of London Dock wall.

One of the many delightful aspects of her service was her genius for bringing other members of her family and clan into it. Her fellow workers will not readily forget the frequent appearances of the Hallward and Hoare connection laden with country produce for decorations or sustenance.

All those who loved her, and in forlorn and hesitating moments loved to lean upon her great strength and firmness of purpose, are thankful that she passed so swiftly and painlessly to the next stage of her service for the Master; but if we dare repine we would fain ask "Lord why so soon?" J.C.P.

The Bishop of Stepney, Henry Mosley, wrote on 27 March 1926

"My dear Rector, I wish I could have been with you and your people tomorrow evening, but it is impossible. St. George's parish has had in Miss Hallward one for whose presence, influence and work they will always thank God. Those who like myself have known her at all intimately will say: "Every thought of her is blessed, every memory good." Her love, her influence, must continue. Death cannot destroy them. There is the momentary shock and bereavement, but in Christ there is greater love, life and service. Tell her many friends how real is my sympathy with them. Yours very sincerely, HENRY STEPNEY."

Miss G. Turner (1925-28)

Miss Turner came in May 1925 with the new Rector C J Beresford, and lived above the Mission House at 136 St George's Street [later 181 The Highway]; she finished regular work in the parish in August 1928, but returning once a week to help with Care Committee and to continue her collecting for the Bank.

Miss Gladys F. Stone (1928-30)

In the magazine for September 1928 the Rector wrote "Miss G F Stone hopes to begin her work in the Parish on September 15th. She was trained at St. Christopher's College, Blackheath, and brings to her work a wide experience both at home and abroad.... She too lived at 136 St George's Street." In the magazine for July 1930 he wrote "Everyone will regret that Miss Stone feels it necessary to seek less arduous work, and will be leaving us about the middle of July. We owe her much for her faithful and kindly work throughout the parish, and it will be very difficult to fill her place, especially in the Kindergarten and with the Brownies, We shall all hope that she will find happy work and better health in the West London parish to which she is going." This was St Thomas' Shepherd's Bush.

Miss E. Burn (1930-34)

Miss Burn replaced Miss Stone at the Mission House, and took over her work. In Sptember 1934 the Rector wrote "Miss Burn will be leaving us at the end of September. She will be sadly missed by the many friends she has made in the Parish during her four years amongst us, and will carry with her the good wishes of all for whatever work she may go to. She has hopes of being able to give her services in some bits of the work here, but this will of course depend upon the demands made upon her by whatever her new work may be. Her going means the going of Miss Cattell too, but she also has kindly offered to continue some of her much valued work with the Brownies. So our farewells to these two ladies will be cheered by the hope that we may not lose them altogether."

Sister A. Reason (1934-??)

A Church Army sister replaced Miss Burn from October 1934, coming from south Wales, though she had previously worked in Hoxton.

Nora Kathleen Neal MBE (1943-??)

Nora had trained for parish work at St Andrew's House, and served as a licensed worker in Hackney before coming to St George-in-the-East. She arrived in 1943, to join the wartime team under Fr Groser that was maintaining ministry to a blitzed and struggling community. Her home was at St John's House, 13 Christian Street. Among other things, she ran a club for girls.

In 1957 (officially licensed the following year) Nora became the first worker at Church House, Wellclose Square with Fr Joe Williamson, having first spent a period doing additional training in 'moral welfare work'. Initially she lodged with Mrs Maaser at 4 Wellclose Square - more than once giving up her bed to a young girl off the streets - but in due course moved into Church House itself. (Curiously, she is listed in diocesan archives of the period as 'Miss D.J.H. Neal'.) In the following year, as the work expanded, she was joined by Daphne Jones (see below).

Nora began retirement as warden at Megg's and Goodwin's Almhouses (founded by Meggs in Whitechapel Road in 1658, 'repaired, improved and further endowed' by Benjamin Goodwin and rebuilt in 1893 in Upton Lane, Forest Gate). She returned to Stepney, first to a bedsit in Tredegar Square and then to a flat at Toynbee Hall, where, as Olive Wagstaff says, she was a great help and encouragement to all her friends and neighbours. At the ago of 80 she moved to Compton Durville in Somerset, the mother house of the Community of St Francis - she was a Franciscan tertiary for 46 years. She played an active role in the House, helping novices and visitors, and when she died there, aged 91, was buried in the grounds.

Daphne Jones

Daphne Jones was a parish worker at All Saints Poplar for an astonishing 55 years - for a few of which she was 'on loan' to St Paul's and the work at Church House Wellclose Square. In her time she served with six rectors and about sixty curates. She was born in 1915 into a rather grand family at Morgan Hall in Fairford, Gloucestershire (where she ended her days: see this interview); her father lived the life of a country gentleman, and social life was dictated by the niceties of calling cards. This meant that in later life she was at ease mixing with the 'great and the good' when their help was needed. Her Anglo-Catholic boarding school in Bexhill-on-Sea supported a mission in the Euston area, and she was inspired at confirmation by Fr Basil Jellicoe, founder of the St Pancras Housing Association, to 'do something'. During the war, she trained as a nurse at St Thomas' Hospital, and ran a 100-bed unit for battlefield victims at Chertsey. in 1946, Mark Hodson, Rector of Poplar (later Bishop of Hereford) invited her to join his staff; meanwhile, she had trained as a midwife and Queen's Nurse, and was soon part of a team providing services across the whole borough, with 6,000-7,000 visits a year. She remained in touch with many of the families for the rest of her life.

A new ministry opened up to her when at a bus stop she met 'Mary', a young Irish girl, heavily pregnant and with no hospital bed booked. Daphne went 'home' with her - a room over a cafe shared with five Indians. This was her introduction to the brothels of Dockland, and the cause of her accepting Fr Joe's invitation to join his 'rescue' ministry. Like him, she remained in contact with many of the girls and their babies (including the original Irish girl's baby).

She - like Nora Neal above - was a member of the Franciscan Third Order, and lived in great simplicity. She was undoubtedly one of the heroines of the East End, and features in the Poplar Saints Memorial Icon.

The story of 'Mary' features in a fictional but semi-autobiographical account of East End midwifery in the 1950s - Jennifer Worth Call the Midwife (Merton Books 2002, Phoenix 2008). The chapters on Cable Street are dedicated to Fr Joe and Daphne Jones. The religious community where she lived and trained, which in the book she she calls 'St Raymund Nonnatus', was in fact the Nursing Sisters of St John the Divine, founded from King's College Hospital in 1848 and one of the few sources of skilled midwifery in the period when the profession was not taken seriously (this changed with the 1902 Midwives Act). They were active in Poplar from at least the 1880s, and provided a borough-wide service in the days before Stepney Council took over responsibility in the years after the Second World War. Daphne Jones did some of her training with them; one or more of them was on the staff of the parish church. They were popularly known as the 'Bluebags' because of their habit.

Jennifer Worth, who died in 2011, also wrote Shadows of the Workhouse (2005), an account of the period when the workhouses were closed but their ethos and practices lingered on, and Farewell to the East End (2009), with further tales of midwifery.

Dorothy Halsall MBE

Dorothy Halsall served here for a year with Fr Groser, before moving with him to the restored Royal Foundation of St Katharine, becoming one of the original members of the community there; she died in 2010 at the age of 98. Here is a tribute from Mary Whybray who (like Olive Wagstaff) was a close friend until Dorothy's death in 2010. Mary was living in Canada at the time, and produced this for her daughter (and Dorothy's god-daughter) Elizabeth to include at Dorothy's funeral: